![]()

As someone who has spent a significant portion of my life immersed in the world of cinema and television, I find the story of how American shows took over Japanese airwaves to be a fascinating tale of cultural exchange and adaptation. Growing up in the 60s, I remember watching many of these iconic shows like Gunsmoke, The Untouchables, and Superman, never imagining they would become popular in other parts of the world, let alone Japan.

In just a short span of time, a small, secluded nation transformed into a significant center for the entertainment world and a sanctuary for aspiring actors and musicians seeking an audience, largely due to the “Big Five” and the popular western series, Gunsmoke. At that time in the late ’50s, Japanese entertainment was plagued by competing studios and unions engaged in constant conflict, resulting in very little content for new TV owners. This lack of programming was a self-inflicted problem caused by the five dominant film studios. If you find show business scandalous today, just imagine the chaos 70 years ago when Japanese film studios engaged in literal gang wars, using extortion to undermine the growth of television networks. In the end, TV triumphed.

Their master plan had peculiar repercussions. The expression “Big in Japan” is typically a back-handed compliment, springing up in the English-speaking media in the ’70s to describe bands or actors who can only find lasting adoration in Japan, not at home, best exemplified by the fictional band Spinal Tap. The origin is murky, but we can trace back the exact year and reason the Big in Japan trope came into existence. The glut of foreign television flooding into Japan showcased different types of genres, cinematic styles, and acting/writing techniques, naturally a great opportunity to study and analyze Hollywood, and some of the content the viewers gravitated toward defied explanation.

For many decades, revamped versions of the dialogues were transmitted nationwide, becoming a constant for people who knew little about the Old West or Midwestern suburbs. These broadcasts, much like samurai films in the West, satisfied an exotic longing, or functioned as advertisements showcasing the opulent lifestyle associated with the American Dream. It wasn’t long before these US reruns gained a level of prestige comparable to HBO. The quality of American productions during that time was unrivaled, even if not all shows were massive successes in their original run in the U.S.

Japan’s Appetite for Western Entertainment

1940s Japan presents a culture that Miyazaki enthusiasts, Ōshima devotees, and manga fans might not relate to. Compared to the diverse and acclaimed films they would create in the second half of the 20th century, their early work was relatively unexceptional. A glance at any list of top Japanese films will reveal few productions before 1949. At that time, Japanese production companies lacked the same degree of creative freedom, scope, and ambition as their contemporaries, which led to a scarcity of special effects, thought-provoking themes, humorous comedies, and giant monster movies.

It appears that a deep fascination with Western media, encompassing both mainstream and lesser-known content, has been present in Japan since before World War II. However, the war served as a pivotal moment, facilitating a surge of influence from American cartoons into the country. For instance, the film “Fantasia,” which was met with significant disappointment domestically, gained immense popularity across the Pacific. As stated by author Matt Alt in his book “Pure Invention: How Japan Made the Modern World“, this film inspired numerous animators and writers within Japan.

1941 found me, a movie reviewer amidst war-torn times, privy to an intriguing tale. A copy of the enchanting film, Fantasia, had been captured on an American transport ship and screened for our propaganda filmmakers. The objective was clear: understand the enemy better. Little did they know that this cinematic masterpiece would leave a lasting impression.

Despite the Japanese affection for Disney movies, Donald Duck comics, or Raymond Chandler books, acquiring these items wasn’t simple. For years, there was no means to watch American television at all. However, this situation would swiftly alter due to a single hasty decision.

The Failed Conspiracy to Kill Network TV

Three short years into the world of TV broadcasting, the competition for viewers intensified dramatically. Without any reliable tool or metric to quantify our audience size back then, every network claimed they were the kings of viewership. Admittedly, there might have been some exaggeration in those claims (compared to today’s streaming platforms who keep their viewing figures under wraps), but the movie moguls, riding high on a wave of international success, couldn’t resist getting drawn into the fray.

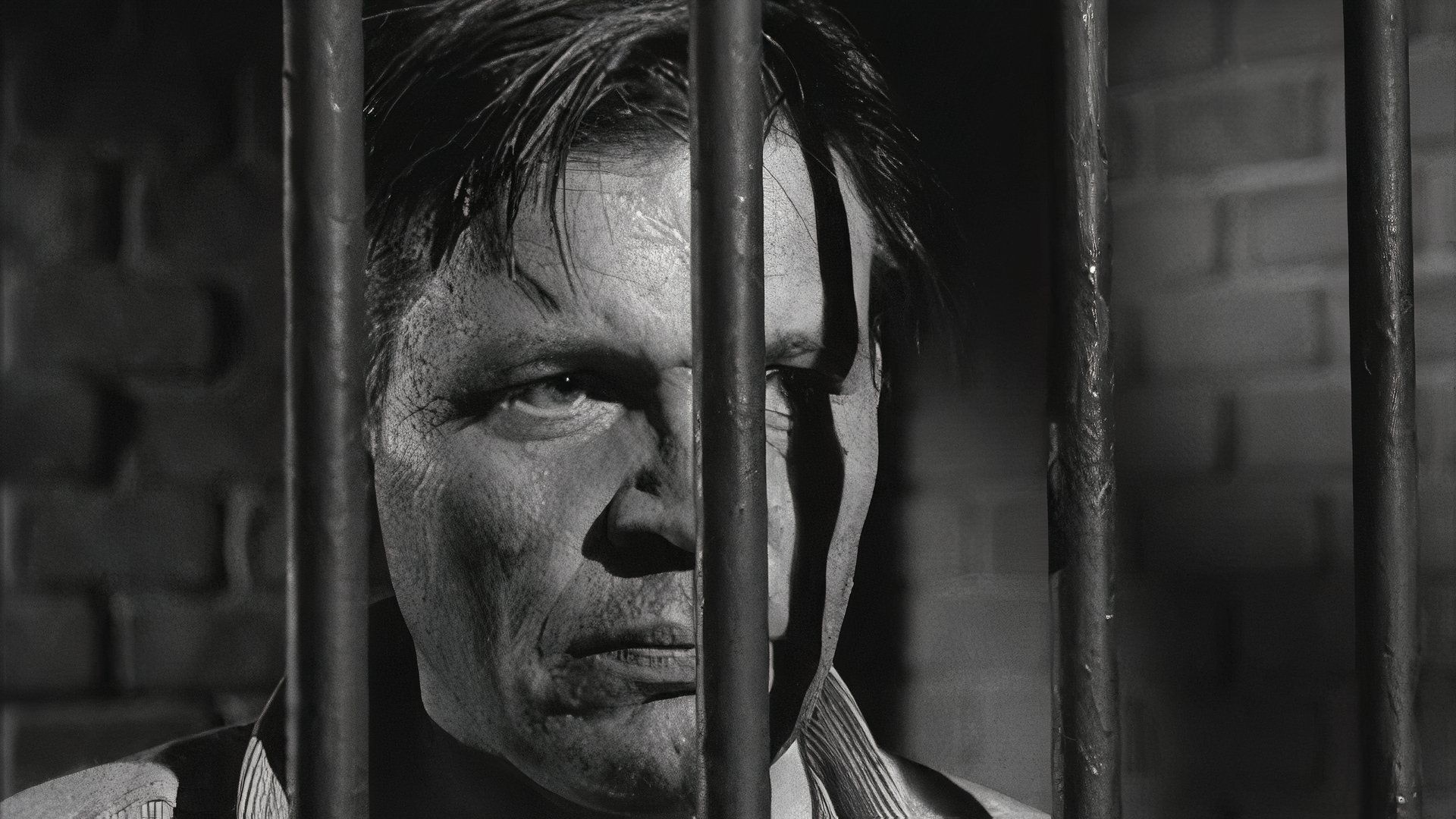

For decades, I’ve been amazed by the underhanded tactics some studios employed in their competitive landscape. Matters escalated significantly during the ’30s when one studio resorted to hiring a mobster to disfigure a popular actor, Kazuo Hasegawa, who had joined a competing film company. To protect their pool of talent and starve competitors in the television industry of content and bankable stars, five major film companies (Daiei, Shin Toho, Shochiku, Toei, and Toho) met in 1956, as reported by NHK. A sixth company followed suit a couple of years later, agreeing to boycott television, sending a clear message. It’s uncertain if these practices were ever deemed legal. Interestingly, this is a stark reminder of why centralized power and monopolies can be detrimental to artists and consumers alike.

Under the name Five Studio Accord, no member from these gatherings in the smoky room was prepared to let their films or contracted actors appear on television, risking being shunned. In an attempt to fill the void left by this decision, TV programming executives turned to American distributors for assistance. A year later, Japan found itself flooded with American successes, “I Love Lucy” being one of the early examples, followed by more specialized shows such as “The Twilight Zone”. Interestingly, by the seventies, Japanese movies were struggling financially overseas, a mere shadow of their past prestige, while the networks continued to prosper.

How Cowboys, Superheroes, Gangsters, and Housewives Took Over Japanese Airwaves

1964 stood as the pinnacle of Japanese cultural assimilation in art, as noted by author Bruce Stronach in his book “Beyond the Rising Sun.” Notably, one of the most frequently cited examples of Japanified American pop culture from ’60s narratives was the long-running western series, CBS’s Gunsmoke, starring James Arness. Some other syndicated shows that gained a significant international following during this period were: The Untouchables, Father Knows Best, The Lone Ranger, Perry Mason, Superman, Lassie, 77 Sunset Strip, The Donna Reed Show, and Alfred Hitchcock Presents.

Japanese viewers preferred their own unique programming tastes, and two Western series in particular – Rawhide and Laramie – became massive hits among them, surpassing the long-running favorite Gunsmoke. Remarkably, Rawhide held a staggering 35% of its time slot. Despite these impressive figures, it was eclipsed by Laramie, which captured over 40% of viewers during its broadcast, according to the networks’ claims.

Occasionally, Japanese producers created American sitcoms of their own, featuring American-born actors who spoke Japanese instead of being uncomfortably dubbed. A notable instance is the show Tokyo Blue Eyes Diary, which closely mirrored its original counterpart. It embraced pro-American sentiments, traditional gender roles, and subtle product placements – including a dairy company sponsorship, an unusual sight when it was published in the 1959 issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Despite primarily being designed for selling cheese, it has additionally fostered a stronger bond between Americans and the Japanese, without burdening U.S. taxpayers with any costs.

After the Five Company Agreement, which was once seen as a formidable obstacle, disintegrated due to financial difficulties faced by the movie studios, its effects continue to be felt. In retrospect, this incident turned out to be beneficial for Japan and the world at large. Actors and singers found fresh avenues for their talents, while consumers were introduced to new forms of entertainment. For instance, films like Disney’s “Rascal” remain popular in Japan even after half a century, demonstrating the ‘big-in-Japan-and-unknown-elsewhere’ phenomenon. Similarly, Japanese anime and live-action TV programs, such as “Super Sentai” and “Takeshi’s Castle”, were adapted and localized for American audiences, becoming “Mighty Morphin Power Rangers” and “Most Extreme Elimination Challenge”. This exchange of culture has now come full circle.

Read More

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Former SNL Star Reveals Surprising Comeback After 24 Years

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- Black Myth: Wukong minimum & recommended system requirements for PC

- Box Office: ‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Stomping to $127M U.S. Bow, North of $250M Million Globally

- Hero Tale best builds – One for melee, one for ranged characters

- Mech Vs Aliens codes – Currently active promos (June 2025)

2024-09-28 21:32