As a film enthusiast who has spent countless hours poring over the works of directors from different eras and countries, I can’t help but marvel at the intricate dance between art and propaganda that has played out throughout history. From the glossy recruitment ads masquerading as movies produced by the US Defense Department to the heavy-handed, one-note films churned out under Soviet rule, it’s fascinating to see how governments have sought to manipulate public opinion through cinema.

As a movie enthusiast, I’ve come to realize that many classic films carry hidden messages, often serving as political commentary or propaganda. For instance, the iconic film Casablanca was primarily produced to stir up political agitation. Look at war movies such as Wings, The Green Berets, and American Sniper, or any other film from any era, and you’ll find the influence of Uncle Sam lurking behind the scenes. Even action films like Transformers aren’t immune to this trend. Propaganda can be both straightforward and intricate. While the motivation for creating such films is often driven by financial factors, such as funding or cost-effective use of props, the production process can become murky, with filmmakers finding themselves bound by numerous conditions. This collaboration comes with a hefty price tag – strings attached and a lingering sense of taint.

Movies intended to advocate for a particular cause, institution, or ideology are often referred to as “propaganda.” This term is commonly associated with works of art that receive support from governments, official military liaisons, or similar entities. Such productions can be found in countries all around the world. For instance, the Chinese blockbuster The Battle of Lake Changkin, despite its shallow and corny aspects, is a prime example of propaganda, reaching a vast audience. A more fitting term might be “captive” audience, as we’ll discuss further below.

Stories against war are less common due to two main reasons: the risk of being imprisoned and the issue of financial resources. For instance, Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier found success by producing propaganda for the Shah of Iran and Reverend Sun Myung Moon respectively, even if the films were not particularly good. In simpler terms, creating propaganda is financially rewarding, regardless of the quality of the movie. Starting a film career can be achieved by associating with military or industrial complexes or local dictatorships (which might be the only option in some places). It’s certainly more appealing than renting a tank. However, authenticity is essential, but at what price?

Uncle Sam’s Prolific Executive Producer Credits

If you’re aiming to be a director or producer and require some guidance on filming with the US Department of Defense, it’s not overly challenging to secure clearance. However, there’s a caveat: you must adhere to detailed regulations outlined by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Public Affairs.

According to the Federal Register, as stated by the US DoD, it’s essential for service members and their branches to be portrayed in a positive and truthful manner in § 238.4. This means showing an accurate representation of the Military Services and the Department of Defense, including Service members, civilian personnel, events, missions, assets, and policies. For instance, Roland Emmerich’s Independence Day was not granted cooperation because a character had a relationship with a stripper, demonstrating this standard procedure. While whether a fighter pilot dating a stripper is realistic or not is subjective, it serves as an example. Larry Taylor explains in Tony Scott: A Filmmaker on Fire that collaborating with a military institution inevitably involves making compromises on artistic decisions, as both parties must balance each other’s interests.

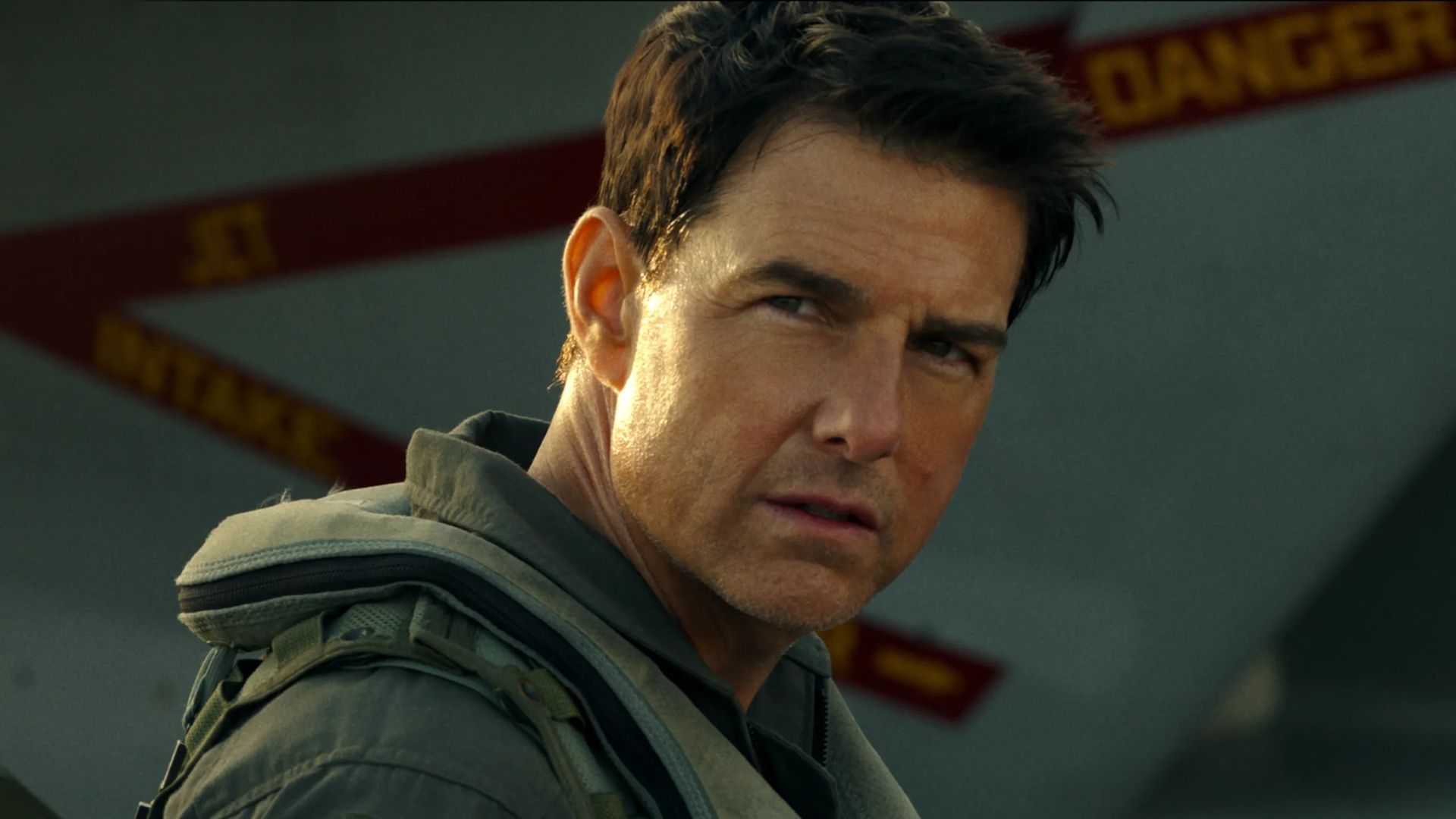

Although the navy couldn’t overtly promote the movie [Top Gun] through their promotional materials, they still found ways to leverage it indirectly. On one side, the assistance provided by the navy greatly enhanced the film’s authenticity in terms of technical and visual aspects; conversely, certain messages were toned down or sanitized.

The laws have roots in wartime propaganda in both the UK and US during World War II, but they haven’t been without resistance from journalists and some veterans. War films such as “Black Hawk Down” are often criticized for distorting true events to make them simpler. Part of this simplification is due to the necessity of condensing real events into a two-hour film, while some of it results from contractual agreements. In essence, you can expect plenty of extras and armed humvees from Uncle Sam, but be prepared for him to also bring along suggestions and requests for edits.

In the movie Goldeneye, the character of a victim in a honeypot operation was changed, upon request from the Pentagon and French Navy (who were supplying materials for the film), from an American to a Canadian character to avoid offending either of the film’s main backers. This amusing tale is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the complex and disturbing world of propaganda.

In Soviet Union, Film Shoots You

As a movie enthusiast, I can’t help but chuckle at the criticism aimed at the US Defense Department for their involvement in turning films into recruitment ads. However, let me clarify that in many other countries, you don’t exactly have the freedom to choose. For instance, during the Soviet era, films were heavily regulated and controlled. They had to portray leaders, military personnel, and workers in a positive light, or else you’d find yourself digging for asbestos in Siberia! That’s why iconic war films like ‘Apocalypse Now’, ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’, ‘The Bridge’, and ‘Casualties of War’ were never made in the USSR.

The same applies elsewhere; China enshrined propaganda into their cinematic culture, now compulsory for all theaters to screen nationalistic films. In North Korea — where the media, military, and state are one and the same — you get such curiosities as the Godzilla knock-off Pulgasari, a cult classic made by a kidnap victim, which is only memorable for being propaganda. China’s iron grip on culture is so strong that it can even intimidate foreign studios to edit their films as to not ruin their manicured narrative of reality. Western auteurs like Jean-Luc Godard and Pier Pasolini might have loved Mao, but they wouldn’t have lasted long under his rule had they really known what artists had to deal with under 24-7 government censorship.

Art for the Masses … PR for Dummies

Good news, propaganda isn’t just for state actors. Now any random person with some spare cash can make it rain. Rev. Sun Yung Moon, a tax-cheat & self-professed messiah, made his fantasies a reality when he enlisted some of the greatest actors and crew to make his infamous flop, Inchon. It starred the greatest living actor of his era, Sir Laurence Olivier, and was directed by former 007 director Terence Young — ironically coming off a TV series about Saddam Hussein, written by Hussein.

In this rephrased version, let me say: The Shah of Iran enlisted Orson Welles, the struggling filmmaker, to serve as his hype man, narrating the questionable choice, Flame of Persia. This production was intended to showcase the Shah’s opulence and magnify the grandeur of his 1971 celebration marking 2500 years of Iranian monarchy. However, instead, it exposed the depth of corruption and extravagance that ultimately contributed to his downfall in 1979. Propaganda, as it turns out, can be costly and dangerous, wielding a two-edged sword that could backfire. This is an observation you’ll often notice.

In an attempt to boost the reputation of his private security company (often referred to as mercenaries), Yevgeny Prigozhin, now known as “the late” Prigozhin, drew inspiration from Soviet times when he produced a pro-war film titled “The Best in Hell“. Contrary to popular belief, this movie had no connection to the conflict in Ukraine or his personal political aspirations. Given the title change, it’s clear that creating propaganda can be a challenging endeavor. Interestingly, many of the patriotic films released in Russia over the past two years following their invasion of Ukraine have received unfavorable reviews from critics and moviegoers alike. Despite a century of success, it seems that movies with insincere or jingoistic themes may not be as popular anymore. However, as audiences become more discerning, governments will likely become increasingly cunning in their propaganda efforts.

Read More

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Former SNL Star Reveals Surprising Comeback After 24 Years

- Gods & Demons codes (January 2025)

- Maiden Academy tier list

- Superman: DCU Movie Has Already Broken 3 Box Office Records

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

- Hero Tale best builds – One for melee, one for ranged characters

2024-11-24 23:32