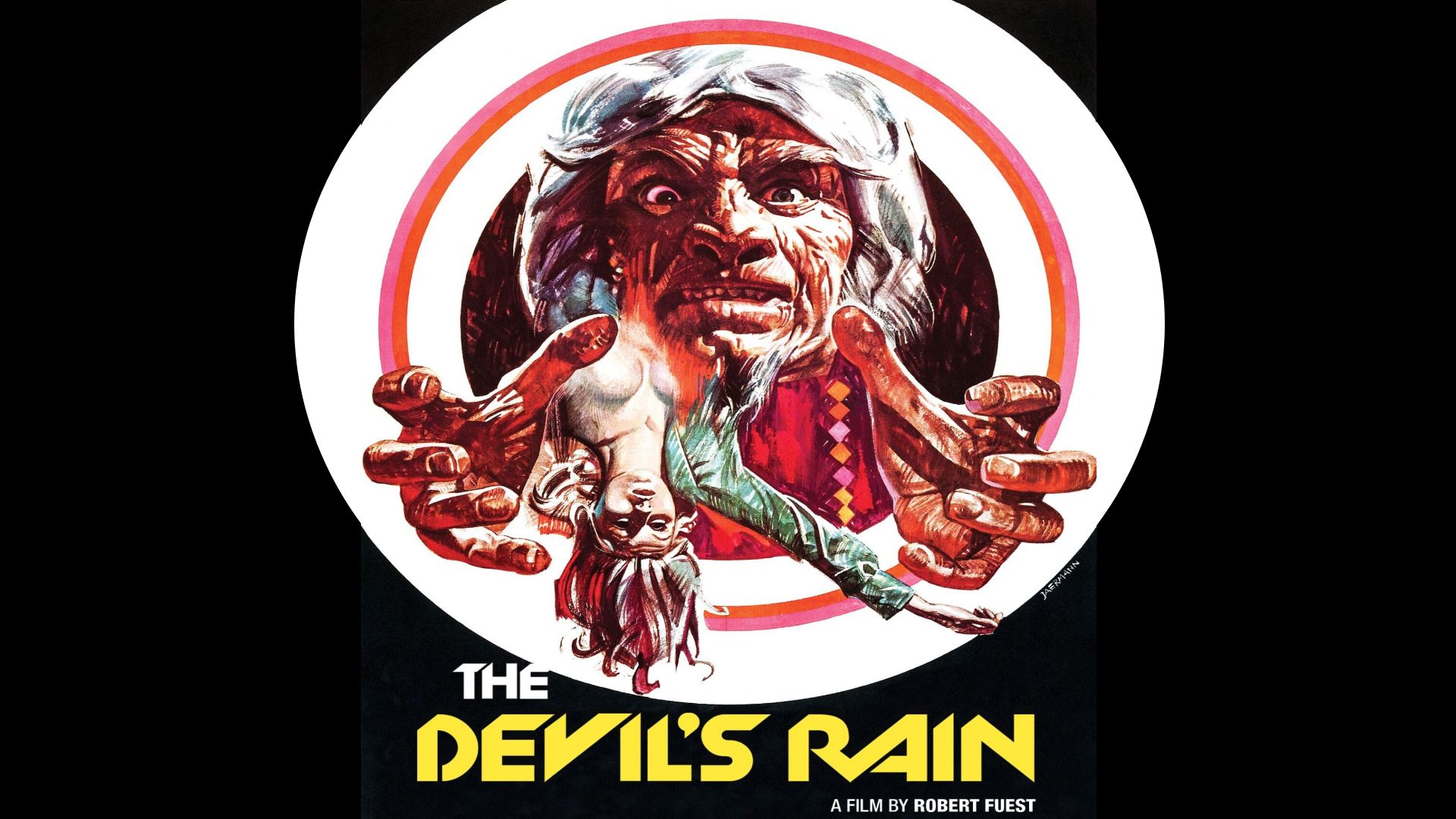

As a connoisseur of B-movies and a student of the history of Satanic panic, I find myself intrigued by the 1975 film, “The Devil’s Rain.” This movie, much like a black cat crossing my path or a full moon on a stormy night, has an undeniable allure that draws me in.

Roger Ebert was undeniably the most esteemed critic in the film industry, yet some movies he disliked and placed on his “most hated” list have gone on to be beloved cult classics. One such movie is “The Devil’s Rain,” which came out in 1975 and featured a star-studded cast including Ernest Borgnine, William Shatner, and John Travolta in one of his earliest roles. Despite Ebert’s negative opinion, this film boasts an impressive ensemble in front of the camera as well as behind it, with Anton LaVey, founder of The Church of Satan, serving as a technical advisor.

The movie “The Devil’s Rain,” although dramatic and somewhat heavy-handed in its portrayal, seems strikingly prescient about the events that unfolded in the 1970s and beyond. The Satanic panic and rumors of ritual abuse became common topics on daytime talk shows and tabloids. Across Middle America, fears of secret cults operating covertly were very real. In “The Devil’s Rain,” the tale of an ordinary American family pursued by a Satan-worshipping cult might have been dismissed as mere entertainment at the time, but such sensational stories would become prevalent throughout the 1980s and even persist into the early 1990s.

The Epic Battle Between Good and Evil

The conflict between goodness and wickedness lies at the heart of most stories and belief systems, and this is no different in “The Devil’s Rain” where the battle is represented by Jonathan Corbis (Ernest Borgnine) going up against Mark Preston (William Shatner). Corbis, acting as Satan’s emissary on Earth, has been chasing the Preston family since the colonial era of America.

Upon initial viewing of “The Devil’s Rain”, one might perceive it as cheesy, somewhat absurd, and even comical. Especially its opening act, which depicts Mark Preston’s faith being destroyed by Corbis and his cloaked followers in an environment reminiscent of a carnival side show. The acting styles of Shatner and Borgnine, particularly Shatner, may appear more comedic than terrifying as they embody their characters.

In contrast, the backdrop and portrayal of evil dating back to the colonial times provide an opportunity for subtle social critique. The scene where Corbis and Preston face their trial by faith, you might say, unfolds in a deserted town. Those versed in Western movie tropes will immediately recognize this type of environment. It’s a common trope where a cowboy or rancher arrives in town to confront the villain, be it an outlaw or rustler.

In colonial America, the ongoing feud between the Preston family and Corbis, dating back to the early American era, mirrors the deep-rooted connections with Puritan beliefs. The presence of witch hunters in this time period, along with an ancient book that carries the signatures of its owners in blood, echoes the rich tapestry of folklore associated with witchcraft and devil worship. By incorporating these elements into a modern context, The Devil’s Rain reimagines these age-old tales and superstitions for a new generation.

The Psychodrama of Ritual

By bringing Anton LaVey on board as a technical advisor and cast member for The Devil’s Rain, the film could draw upon some aspects of Modern Satanism, particularly the psychodrama of ritual. Established in 1966, LaVey’s Church of Satan was not centered around any traditional or primitive devil worship but rather catered to fulfilling fundamental desires. In essence, many of the beliefs espoused in LaVey’s Satanic Bible align more with Nietzsche’s philosophies, such as celebrating the Dionysian, rejecting religion, and indulging the self. The concept of Psychodrama, which stimulates the senses through visuals and atmosphere, shares similarities with the intense content viewers experience in The Devil’s Rain.

Ebert’s critique of The Devil’s Rain pointed out that its storyline was incredibly slim, as he expressed, “If only the movie weren’t so painfully dull. It’s stretched too thin, with not enough material for a full-length film.” However, the film’s focus on style over substance is symbolic of an intense, immersive ritual, much like a form of psychodrama for the senses.

The vibrant hues and pipe organ music that underscore the rituals enacted by Corbis and his congregation in the movie, along with the jaw-dropping climax further accentuated by practical effects, create an engaging experience that keeps viewers glued to their seats. Although “The Devil’s Rain” may not be a flawless film, its stylized portrayal of devil worship and the imposing presence of evil captivates audiences, making the iconic horned villain even more alluring. As LaVey himself put it, this character has managed to maintain interest in the church for many years.

Not Too Serious and Still Enjoyable

In essence, what does The Devil’s Rain teach us? Released the same year as Jaws that made people fear the water, and Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom, which exposed the hypocrisy of power and the oppression of masses, it followed closely after William Friedkin’s chilling portrayal of a fierce struggle between good and evil in The Exorcist. This suggests that The Devil’s Rain was expected to meet high standards.

While Ebert might have held disdain for the film, there’s something utterly enjoyable in how The Devil’s Rain doesn’t take itself too seriously and allows us to revel in the ham-fisted performances and effects that might seem laughable by today’s standards. If nothing else, with the nostalgia that surrounds the era of Satanic panic in popular culture, we can look back at The Devil’s Rain and have a hearty laugh to ourselves at the prospect of these fears and moral hysteria ever coming to life. Stream on Tubi or Shudder.

Read More

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Black Myth: Wukong minimum & recommended system requirements for PC

- Gold Rate Forecast

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Former SNL Star Reveals Surprising Comeback After 24 Years

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- Arknights celebrates fifth anniversary in style with new limited-time event

- Gods & Demons codes (January 2025)

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

- Maiden Academy tier list

2024-12-15 23:01