As a fan following the thrilling world of true crime, I’ve noticed that this genre is filled with contradictions – it educates while also exploiting, enlightens yet sensationalizes. Over the past decade, it has transformed into a cultural obsession, expanding from late-night Dateline specials to prestige TV, cinematic documentaries, and popular podcasts. However, when do we reach a point of saturation where these tropes become repetitive and start to collapse inward?

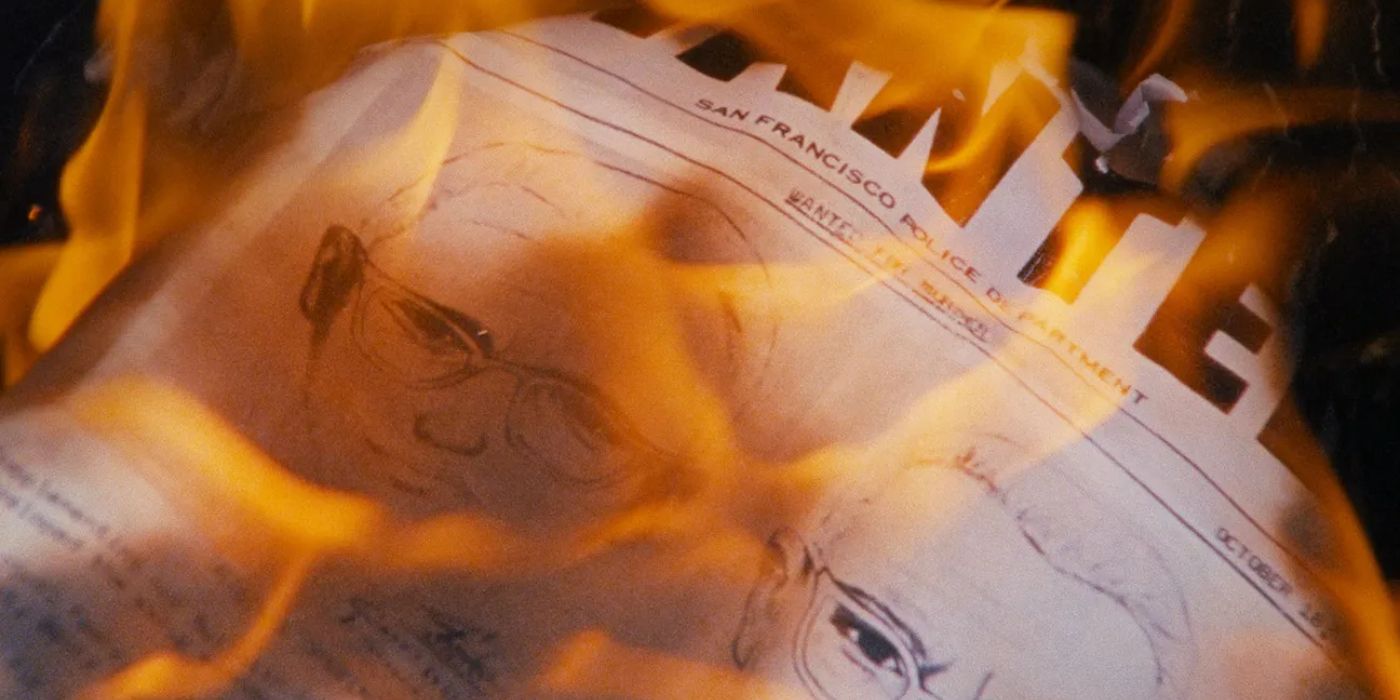

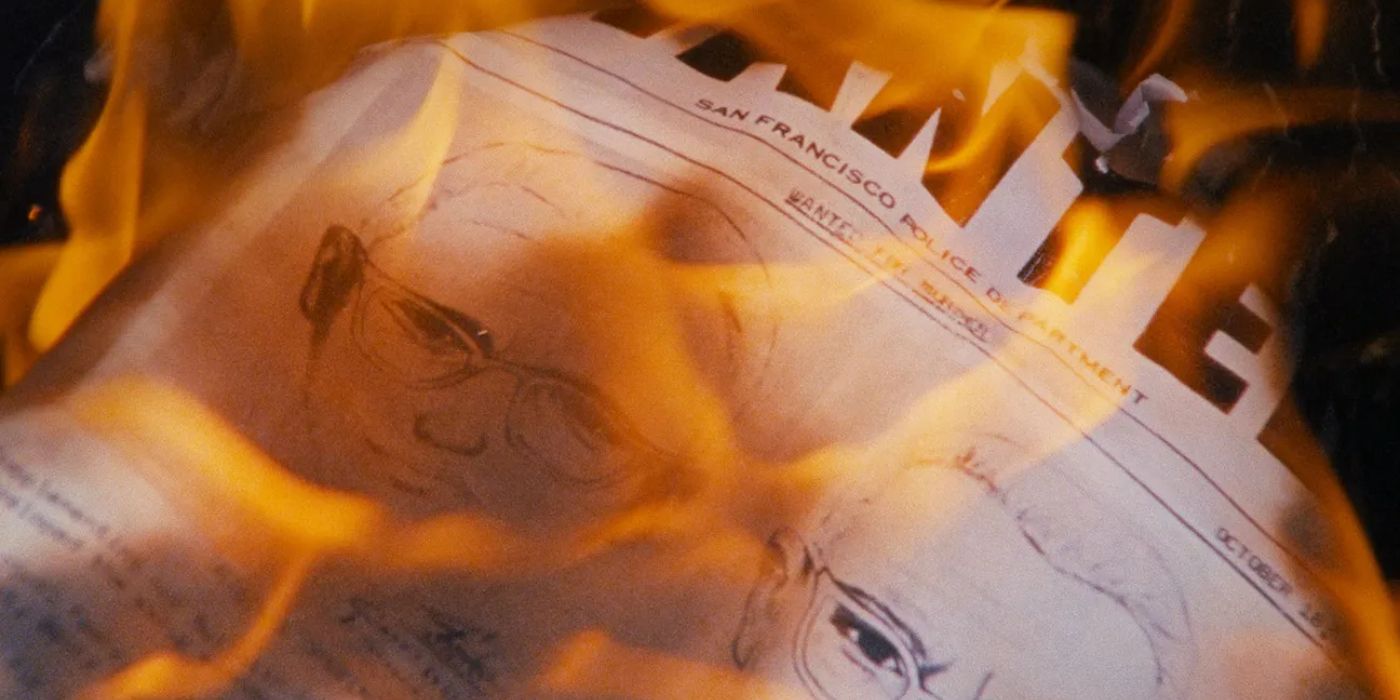

The latest offering from British director Charlie Shackleton, Zodiac Killer Project, is less about the story of a serial killer and more about dissecting true crime itself. This film serves as an introspective, creatively innovative exploration of why we tell these stories, how they are told, and whether any of it brings us any closer to understanding or closure.

A Documentary That Never Was

The movie begins by slowly panning over an empty American highway, a sight that triggers our minds to anticipate fear due to decades of exposure to true crime narratives. We’re led to believe that something gruesome occurred here; this peaceful roadside location appears to be a crime scene ready for retelling in a foreboding narrative. Shackleton, the narrator, plays along with this assumption, establishing what seems like a typical documentary setup. However, he abruptly breaks his narrative. This isn’t a documentary about the Zodiac Killer; instead, it’s a documentary about a documentary that the Zodiac Killer never made about himself.

From there, Shackleton guides us through the movie he imagines, dissecting the common visual and storytelling patterns in real-time that are typical of true crime genre. Instead of reenactments, he discusses how he would have staged them differently. Instead of using archival footage, he talks about his choices for powerful B-roll. The omission of these elements is significant – the movie not only unveils the illusions in true crime but also challenges if these techniques serve any purpose beyond mere aesthetics.

Shackleton’s intellectual perspective may seem dry at first, but he infuses it with humor and irony. For instance, he jests that generic footage – like slow-motion streetlight flickers or close-ups of unidentified hands sifting through old case files – can be surprisingly impactful. This is because it doesn’t convey specific information. Instead, it sets a mood, using a common visual language that guides viewers into a comfortable pattern. It turns out, the structure of true crime documentaries can sometimes be quite amusing due to its inherent ineffectiveness.

The Limits of True Crime’s Pursuit of Justice

Delving into the heart of it, my exploration – the Zodiac Killer Project – unearths the compelling allure that true crime narratives hold, particularly their pursuit of a definitive ending. The Zodiac case, an enigma shrouded in mystery due to its unsolved nature, has morphed into a symbol within pop culture folklore. I, Shackleton, present you with Lyndon Lafferty – a retired California highway patrolman who tirelessly worked on the case and penned a book titled “The Zodiac Killer Cover-Up: The Silenced Badge” – claiming to have unmasked the perpetrator.

In Lafferty’s narrative, we see a recurring pattern: an individual, acting alone and convinced of his insights that others seem to overlook, relentlessly pursues a theory dismissed by law enforcement. At first, Shackleton portrays Lafferty’s work with the respect often found in true crime narratives. However, as the story unfolds, Shackleton subtly undermines our assumptions, exposing just how shaky the book’s assertions ultimately are.

The balance between fact and storytelling in Shackleton’s perspective extends to his critique of other true crime works like “The Jinx,” where the ethically questionable final scene – featuring Robert Durst seemingly confessing to murder – raises concerns. The moment was kept hidden for how long? It’s troubling to allow a suspected killer to evade justice in order to create an ideal dramatic ending, isn’t it? Shackleton questions whether the true crime genre values storyline development over seeking truth, causing us to wonder if its primary focus is crafting compelling narratives rather than unearthing facts.

The Ethics of Consumption

The Zodiac Killer Project delves deeper than just analyzing the techniques used in true crime, instead provoking us, the viewers, to ponder. What is it that draws us to these stories? Is it a genuine quest for justice or perhaps a fascination with something more sinister? Interestingly, Shackleton points out the ethical flaws in Ryan Murphy’s Dahmer series, particularly its insensitivity towards the victims’ families. Yet, he confesses to having found it intriguing. This instance reflects the film’s candor: unlike other documentaries, Zodiac Killer Project doesn’t claim moral superiority but rather encourages us to confront our own role in this macabre fascination.

As a movie enthusiast, I’d say that one captivating part of the film delves into the epic saga of “Paradise Lost,” a groundbreaking documentary trilogy focusing on the West Memphis Three. Shackleton sheds light on how the public became heavily engrossed in the miscarriage of justice suffered by these teenage boys, yet failed to empathize with the profound sorrow endured by the parents of the slain children. The father of one victim, unfortunately, gained notoriety in this case due to his unstable actions and emotional outbursts, which were frequently analyzed, criticized, and even mocked by spectators.

Shackleton poses an intriguing query: If the father had truly been at fault, would his actions be perceived as less questionable? Would we label them as clear indications of a criminal rather than the raw, unrefined sorrow of a mourning parent? This movie challenges us to examine our prejudices. What does it reveal about ourselves that we choose to empathize with specific forms of suffering, and that we find it easier to comprehend grief when it aligns with our notions of righteousness and wrongdoing?

A Formal Exercise That Is Anything But Gimmicky

Shackleton’s style is similar to that found in experimental documentaries such as John Smith’s “The Girl Chewing Gum,” where the director reveals the upcoming events within a scene ahead of time, thereby highlighting the intricate workings of film direction. Similarly, Shackleton sets the stage by telling us what would have been presented before it becomes visible, thereby emphasizing the constructed nature of true crime narratives.

The film-based project titled “Zodiac Killer” uses a medium traditionally linked with tangibility and authenticity to explore the hollowness of emotionally stirring images. Instead of typical reenactments, it deliberately avoids them, prompting viewers to actively create their own mental pictures from Shackleton’s descriptions. In this way, the filmmaker subtly suggests that true crime narratives frequently depend on our imaginations to complete the story.

The Inescapable Question: Is Closure Possible?

As I delve into the enigma that is The Zodiac Killer Project, one consistent thread becomes evident – the elusive pursuit of finality. This film persistently revisits the notion that true crime, with its meticulously crafted narratives and forensic scrutiny, seldom brings about genuine resolution. The Zodiac case remains an unsolved enigma. The true crime genre appears trapped in a loop of retelling, reshaping, and repackaging ancient mysteries from fresh perspectives. Throughout this endless quest for answers, Shackleton poses a poignant question: What exactly are we chasing?

As we approach the end of the movie, we’ve been thoroughly dismantled as spectators, with Shackleton meticulously removing the conventional framework of true crime documentaries, leaving us in a transitional state – devoid of clear resolutions, without a grand unmasking, and lacking the comforting sense of completion. Perhaps that was his intention.

The Future of True Crime

As a follower of the Zodiac Killer Project, I’ve come to realize it’s not just about dissecting true crime; it’s about pushing the boundaries and shaping the future of this genre. In our present media climate, where murder podcasts and sensationalist documentaries abound, responsible storytelling becomes a challenge. We must navigate between quenching the public’s thirst for these tales and upholding ethical standards that respect victims and their families.

Shackleton, however, doesn’t provide solutions, but instead equips us with something priceless – the capacity to ask insightful questions.

Ultimately, the Zodiac Killer Project is less focused on the Zodiac Killer himself and more on the relentless churn of the true crime industry, transforming grief into narratives for consumption, distorting truth into spectacle. It serves as a critique, a probe, and arguably most crucially, a moment of reflection – a chance to step back and ponder what we’re observing, and why. The Zodiac Killer Project was showcased at the Sundance Film Festival; it will be screened again on Feb. 1. Public access to the online screening will be available from Feb. 1 to Feb. 2. For more details, click here.

Read More

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- Silver Rate Forecast

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- Black Myth: Wukong minimum & recommended system requirements for PC

- Box Office: ‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Stomping to $127M U.S. Bow, North of $250M Million Globally

- Former SNL Star Reveals Surprising Comeback After 24 Years

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Hero Tale best builds – One for melee, one for ranged characters

- Mech Vs Aliens codes – Currently active promos (June 2025)

2025-02-01 03:37