Filmmaking is an artistic expression that transcends borders, yet movies and TV shows may not have the same impact in various nations due to several factors. At a fundamental level, there’s the challenge of translation – whether it’s adding subtitles or dubbing dialogues, the essence and subtlety can shift when a narrative is adapted to another language. Furthermore, there are cases where viewers from different countries may be watching entirely distinct content. Scenes can get removed during exportation of a film or show, either due to government censorship or overzealous distributors. In some instances, productions even create alternative shots for other countries, either to accommodate cultural sensitivities or as hidden treats (Easter eggs).

Sometimes, international viewers encounter unique scenes that were not part of the original production in the show or movie’s home country. In some cases, the creators themselves add this new material to international versions, but usually, it is the international distribution companies who adapt and modify the acquired content significantly. This widespread alteration across different markets is not common practice today, but aficionados of classic B-movies and certain well-known children’s TV franchises might recognize a few instances of this phenomenon.

Looper

Back in the 2010s, I found myself eagerly following Hollywood’s strategies to crack the Chinese movie market. As a fan, I was particularly intrigued by DMG Entertainment, an American firm that specialized in bringing U.S. films to China. Their primary goal was to make Hollywood more appealing to Chinese audiences. One of their most successful collaborations was Rian Johnson’s 2012 sci-fi masterpiece, “Looper,” a film that left a lasting impression on me.

As a seasoned gamer, I, Joe – the self-destructing assassin, embark on a three-decade journey from vibrant Paris to the bustling metropolis of Shanghai. From being embodied by Joseph Gordon-Levitt to morphing into Bruce Willis, this transition is skillfully depicted in a swift yet poignant montage. Initially, this sequence was meant to unfold in the romantic cityscape of Paris, but DMG Entertainment had other plans, suggesting we relocate to Shanghai instead.

In the American version, this Shanghai chapter races by at an alarming pace, but in the Chinese cut, it’s expanded for a more immersive experience. An insider connected to the film shared with the Los Angeles Times that the extended Shanghai scenes didn’t resonate with American test audiences due to pacing issues. However, the Chinese audience, appreciating the richness of these scenes, voiced their preference for them, leading us to accommodate their wishes.

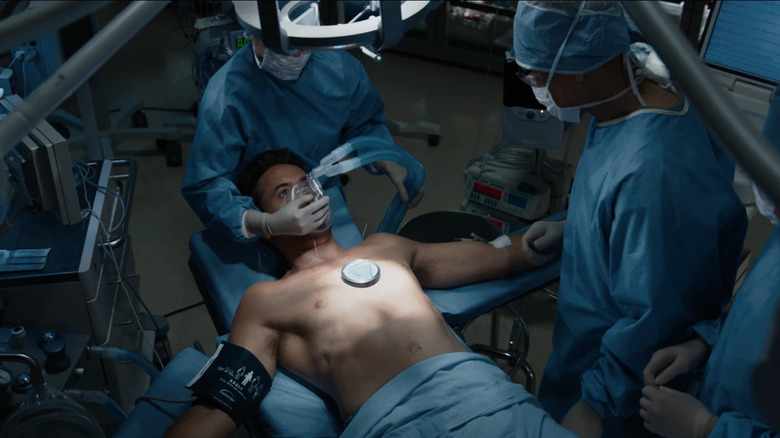

Iron Man 3

Following the release of “Looper”, DMG Entertainment’s highly controversial extended Chinese version of “Iron Man 3” was released a year later, thanks to a collaboration between DMG and Marvel Studios. This special Chinese edition included an extra four minutes of content not seen in other releases. Initially, Marvel Studios had planned to include a China-exclusive post-credits scene in “The Avengers”, either featuring Shang-Chi or the antagonist from “Iron Man 3”, The Mandarin. However, DMG expressed concerns that introducing The Mandarin might lead to their production being shut down.

The additional scenes in “Iron Man 3” featured prominent brand placements for Gu Li Duo milk drinks and Zoomlion heavy industry, along with appearances by Chinese actors Wang Xueqi and Fan Bingbing (who were only visible in the Chinese version). These actors portrayed doctors responsible for removing Tony Stark’s arc reactor from his body. Furthermore, in the Chinese version, the character played by Ben Kingsley was renamed “Man Daren” to avoid any association with Orientalist stereotypes.

The movie “Iron Man 3” was popular in China, yet many Chinese viewers criticized unnecessary additional scenes, and Marvel chose not to participate in any more Chinese co-productions following this film. In contrast, the 2021 release of “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings,” which partly takes place in China, was not screened in China due to controversy surrounding comments made by its star Simu Liu about his parents leaving China.

Godzilla

One well-known instance of a film significantly altered for a different nation is the 1954 movie “Godzilla,” which made its U.S. debut in 1956 under the title “Godzilla, King of the Monsters!” The American version, featuring an English dub, shortened the Japanese original by approximately 40 minutes. Additionally, new scenes helmed by Terry O. Morse were added, introducing a character named Steve Martin (played by Raymond Burr), who is unrelated to the popular actor from “Only Murders in the Building.

Numerous critics have found fault with the film “King of the Monsters,” as it omits ties to World War II and atomic bombs, which might not have displeased director Ishiro Honda much, considering his inspiration from American monster films. On the other hand, actor Raymond Burr sincerely embraced the anti-nuclear theme in “Godzilla.” When he reprised his role for “Godzilla 1985” (the English version of “The Return of Godzilla”), he declined light-hearted lines to deliver a more somber portrayal. The comical parts were instead assigned to other American actors.

Besides the two “Godzilla” films featuring Burr, some other “Godzilla” movies had extra scenes included during their American releases. For instance, “Godzilla Raids Again” was altered to become “Gigantis, the Fire Monster,” and additional stock footage was included. Furthermore, in “King Kong vs. Godzilla,” a new scene featuring a United Nations reporter was added, which presented the action as a news broadcast. Similarly, Toho, the Japanese production company, shot extra footage exclusively for the American version of “Mothra vs. Godzilla.

Power Rangers

Haim Saban and Shuki Levy took Toei’s “Super Sentai” series and made it almost a whole new show when they produced “Mighty Morphin Power Rangers” in 1993. They kept the action scenes with costumed superheroes from the Japanese version, but replaced the out-of-costume parts with American actors. They adapted the stories to fit Saturday morning TV standards and avoided lip-syncing issues in live-action dubs by localizing the dialogue.

Despite some parents expressing concerns over its violence, the television show “Power Rangers” became an unstoppable favorite among American children, ranking at the top in Nielsen ratings during its initial season. This success paved the way for other American versions of Japanese tokusatsu shows: episodes from the “Metal Heroes” series were combined with “VR Troopers” and “Beetleborgs,” “Electric Superhuman Gridman” was transformed into “Superhuman Samurai Syber-Squad,” and various “Kamen Rider” series were rebranded as “Masked Rider” and “Kamen Rider: Dragon Knight.” To this day, 30 seasons of “Power Rangers” have aired on different networks, moving from Fox to ABC, then to Jetix, Nickelodeon, and finally, Netflix.

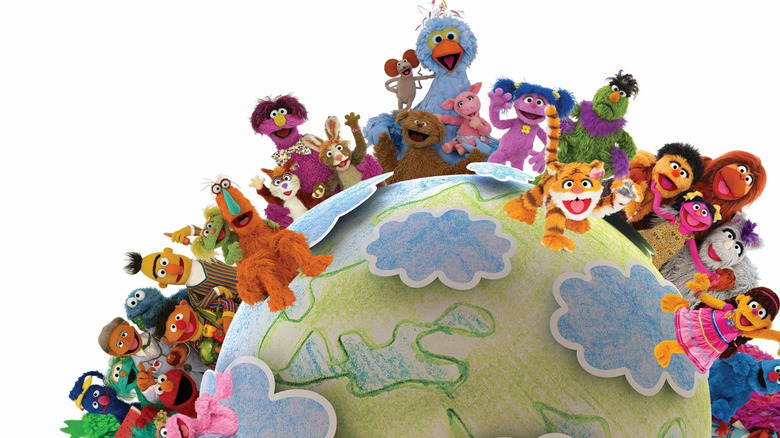

Sesame Street

Initially launched in 1969 as a tool for educating underprivileged American children, Sesame Street gained popularity worldwide. As international broadcasting opportunities arose, the Children’s Television Workshop (now known as Sesame Workshop) established innovative guidelines for adapting educational content to diverse cultures. While some nations opted to simply dub the American version of Sesame Street, others collaborated with CTW to create locally-tailored adaptations. These co-productions blend elements from the original American show, such as skits and songs, but ensure that the primary street segments reflect each country’s unique culture.

Since 1972, starting with Mexico’s “Plaza Sésamo,” a total of 44 distinct versions of “Sesame Street” have been produced globally, each featuring exclusive Muppet personalities. The 2006 documentary “The World According to Sesame Street” delves into the creation process of three international adaptations: Bangladesh’s “Sisimpur,” which aims to address the country’s preschool education deficiency; Kosovo’s “Rruga Sesam/Ulica Sezam,” which promotes friendship among Albanian and Serbian children; and South Africa’s “Takalani Sesame,” which garnered global attention for its HIV-positive Muppet character, Kami.

Global adaptations of “Sesame Street” have been susceptible to changes in political climates. Following the Oslo peace accord in the ’90s, Israel’s “Rechov Sumsum” and the Palestinian “Sha’ara Simsim” joined forces to foster understanding, but funding for the Palestinian version was cut by the U.S. Congress in 2012. Criticisms about supporting Arab “Sesame Street” programs have been made by President Trump.

Fraggle Rock

Drawing from his involvement with multiple “Sesame Street” collaborations, Jim Henson purposefully crafted the initial 1983-87 run of “Fraggle Rock” to offer viewers around the world slightly diverse viewing experiences. While the Fraggle scenes filmed in The Land of the Gorg remained consistent across all international broadcasts, those featuring “Silly Creatures” (humans) from “Outer Space” (Earth) were tailored for individual countries.

As a gaming enthusiast, I’ve delved into various adaptations of this popular game. In the U.S. and Canada, the central figure was Doc, portrayed by Gerry Parkes. Interestingly, in the German version, the role was taken up by Hans-Helmut Dickrow. The French version introduced a unique twist with Michel Baker’s Doc being a baker instead of an inventor. The British adaptation featured a rotating cast of leads, with Fulton Mackay as the lighthouse captain in the first two seasons, his nephew P.K., played by John Gordon Sinclair, taking over in the third season, and Simon O’Brien stepping into the role of B.J. in the final two seasons.

Digimon: The Movie

Following the financial triumph of “Pokémon: The First Movie” by Warner Bros., the team at 20th Century Fox aspired for similar box office victories with their own anime series featuring monsters, titled “Digimon.” However, in the year 2000, no full-length “Digimon” movies had been produced in Japan. As a result, Fox and Saban combined several shorter films to produce “Digimon: The Movie,” which ultimately fell short of the success they had hoped for.

Among these, three were standalone “Digimon” animated shorts, and two of them, “Digimon Adventure” and “Our War Game,” are significant as they were early works from the future Academy Award-nominated director Mamoru Hosoda. However, one short was quite distinct. In its initial run, “Digimon: The Movie” began with a scene featuring the characters from “Angela Anaconda,” a comedy animated series using cut-out animation that was broadcast on Fox Family channel, attending the theater to watch “Digimon: The Movie.

Neither the team behind the “Digimon” dubbing nor the creators of “Angela Anaconda” showed much excitement for this corporate collaboration. Fans of “Digimon” have called the “Angela Anaconda” short a “monstrosity,” and it’s noteworthy that it’s absent from Discotek’s 2024 Blu-ray collection of “Digimon: The Movie.

Godfrey Ho’s Ninja movies

Godfrey Ho has directed a total of 159 films using different aliases, and about one-third of these films have the word “Ninja” in their titles. Some well-known examples include “Ninja in the Killing Fields,” “Ninja Terminator,” “Ninja Avengers,” and “Full Metal Ninja.” However, it’s important to note that Godfrey Ho did not personally film all these movies. Instead, he operates by a technique known as “cut-and-paste,” where he takes footage from various pre-existing Asian action films, combines them with new scenes centered around ninjas, adds English dubbing, and releases these reassembled movies globally.

The results are so poorly made that they have a unique charm, appealing to a devoted fanbase who enjoy them despite their poor quality. Interestingly, these “Ninja” films have gained more popularity than the movies they borrowed content from, which were often left incomplete or unseen. The web series “Ninja: Mission Force,” penned by Megan Rachelle and directed by Ed Glaser, was created as a tribute to Ho’s filmmaking style.

Shining Time Station

A popular method of expanding localization is by integrating British children’s shows within American programming. A notable instance of this is “Shining Time Station,” a PBS series that ran from 1989 to 1995, which served as an entry point for the popular series “Thomas the Tank Engine and Friends” in the United States. Each episode featured a couple of brief “Thomas” stories, enclosed within new tales about children interacting at the main train station.

Initially, Ringo Starr, a former member of the Beatles and the initial narrator for Thomas, portrayed Mr. Conductor – a magical character who introduces the Thomas tales – in the first season. Later on, George Carlin assumed this role in subsequent seasons. The TV series “Shining Time Station” was adapted into a movie titled “Thomas and the Magic Railroad” in 2000. However, the original British version of “Thomas and Friends” eventually gained more popularity in the U.S., airing on PBS, Sprout, Nickelodeon, and Netflix.

Le Reine Margot

Prior to his infamous misconduct towards women being unveiled in Hollywood’s most significant scandal over the past decade, Harvey Weinstein had already garnered a poor reputation due to his practice of heavily editing international films. This earned him the nickname “Harvey Scissorhands.” For instance, in Patrice Chéreau’s 1994 adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’ “Le Reine Margot,” a French-Italian co-production released as “Queen Margot” in North America, Weinstein not only shortened the film by 15 minutes, but also added back a scene that had originally been removed, featuring two lovers enveloped in a red cloak.

In marketing efforts by Miramax, this deleted scene became the main focus, emphasizing the romantic aspects while minimizing the intense violence. The abridged version of “Queen Margot” was successful enough in America to secure a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the Golden Globes and a nod for Best Costume Design at the Oscars. However, critics who found the extended original version confusing were still left feeling overwhelmed by this shortened version. Eventually, the longer cut received a remaster and an official American release to celebrate its 20th anniversary in 2014.

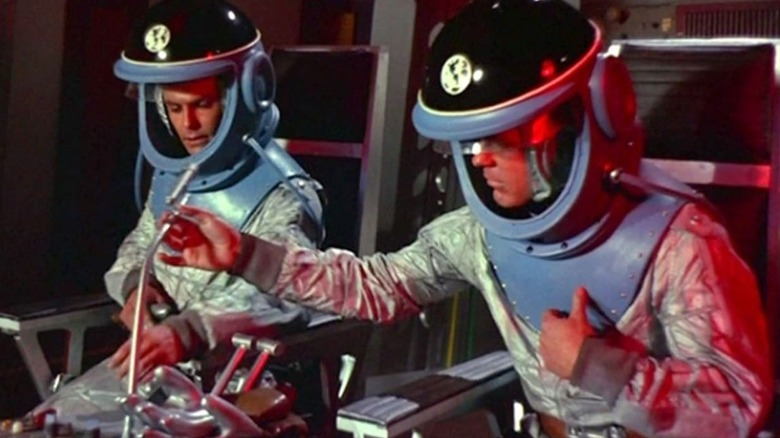

Planet of Storms

1962’s Soviet sci-fi film “Planet of Storms,” directed by Pavel Klushantsev, was reimagined twice by Roger Corman’s American International Pictures. The 1965 English dubbed version, renamed as “Journey to a Prehistoric World,” was adapted for American TV broadcasts. While it largely followed the original storyline, it removed any Soviet references, omitted credit for the original cast, and added new scenes featuring actors Basil Rathbone and Faith Domergue.

1968’s movie titled “Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women,” surprisingly deviated significantly from its original content as it featured prehistoric women, a concept that wasn’t present in the source material. Remarkably, the brief scenes featuring this tribe of scantily-clad Venusians were filmed by Peter Bogdanovich, who is both a film historian and director of “The Last Picture Show,” under the alias “Derek Thomas.

During an interview with The AV Club, Bogdanovich shared that Corman asked him to film some scenes featuring women. American International Pictures (AIP) wouldn’t purchase the film unless there were female characters included. So, Bogdanovich devised a way to include women in the movie and filmed for five days. The footage was later edited into the final cut. Since no one could understand it, he provided the narration himself. Corman refused to allow any sound to be added.

Battle Beyond the Sun

If it seems odd to consider director Peter Bogdanovich inserting rough, homemade scenes into a Soviet science fiction film for Roger Corman, then try envisioning acclaimed director Francis Ford Coppola doing the same thing (and that might not be too difficult to imagine after witnessing Coppola’s 2024 sci-fi catastrophe “Megalopolis”).

The 1959 Soviet film “Nebo Zovyot,” created by Mikhail Karyukov and Aleksandr Kozyr, initially focused on the Cold War space race from a Soviet viewpoint, making it unmarketable in America. In the 1962 reinterpretation by American International Pictures, titled “Battle Beyond the Sun” (distinct from Roger Corman’s “Star Wars” imitation “Battle Beyond the Stars”), the rival global powers were transformed into fictional entities called “North Hemis” and “South Hemis.

Instead of portraying a plausible image of Martian travel as some films do, “Battle Beyond the Stars” incorporated additional sequences directed by Coppola featuring rubber creatures resembling genitals engaging in physical combat. In an interview on Trailers From Hell, Coppola and director Jack Hill, under Corman’s guidance, mentioned that these scenes elicited laughter, which may not have been Francis’ intent, but Roger certainly appreciated it.

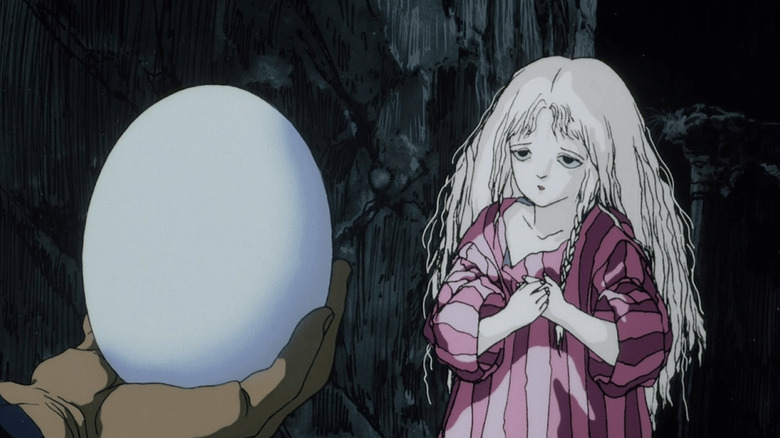

Angel’s Egg

40 years passed without an uncensored American version of the 1985 anime masterpiece “Angel’s Egg,” which was directed by Mamoru Oshii and produced by Toshio Suzuki from Studio Ghibli. However, it was edited along with live-action sequences directed by Carl Colpaert for its 1988 English language release titled “In the Aftermath: Angels Never Sleep.” It is now scheduled for U.S. release in 2025 by GKIDS.

Following its release, “In the Aftermath” was distributed directly to video in both the U.S. and the U.K., with a limited theatrical run in Australia. As detailed in special features on the “In the Aftermath” Blu-ray disc, New World International obtained the rights for “Angel’s Egg,” but Colpaert and producer Tom Dugan found this abstract film perplexing. To provide context to the story, they incorporated live-action scenes. However, the success of their attempt is debatable; as Starbust magazine’s review asserted, this blended movie seems to lack any coherent narrative sense.

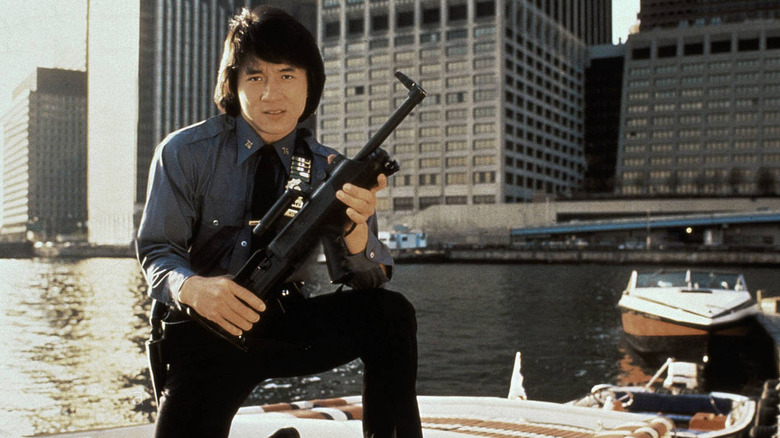

The Protector

1985’s “The Protector” marked Jackie Chan’s second starring role in an American film, following 1980’s “The Big Brawl.” However, the martial arts movie icon was dissatisfied with director James Glickenhaus’ vision for the film. Action movies in America at that time invested less in fight scenes compared to their Hong Kong counterparts. Consequently, during the production of the American version of “The Protector,” Chan was brainstorming ways to re-imagine and elevate “The Protector” according to his standards for the Hong Kong market.

In its edited form, removing explicit and manipulative elements, the Hong Kong release of “The Protector” is four minutes abbreviated compared to the U.S. version. This shorter version, however, includes an additional subplot penned by Edward Tang and starring singer Sally Yeh. Moreover, it features a revamped finale fight scene. A lengthier Japanese adaptation reintroduces some scenes from the U.S. version omitted in the Hong Kong release, making it unique with bonus footage during the credits.

Read More

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Honor of Kings returns for the 2025 Esports World Cup with a whopping $3 million prize pool

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Kanye “Ye” West Struggles Through Chaotic, Rain-Soaked Shanghai Concert

- Arknights celebrates fifth anniversary in style with new limited-time event

- Mech Vs Aliens codes – Currently active promos (June 2025)

- Every Upcoming Zac Efron Movie And TV Show

- Hero Tale best builds – One for melee, one for ranged characters

2025-06-02 15:32