As a cinephile who has traversed the labyrinth of cinema history, I find myself captivated by the enigmatic allure of “The Night Porter.” This film, often misunderstood due to its explicit sexual content, serves as a subversive commentary on the hypocrisy and darker aspects of humanity during the Nazi regime.

Many regard Roger Ebert as one of the most influential figures in film criticism, with Werner Herzog referring to him as a “cinema soldier” and garnering affection from millions worldwide. However, not everyone always accepted his opinions as infallible truth. One particularly harsh critique he penned was for the film “The Night Porter“, which will mark its 40th anniversary on October 1st, 2024. Ebert’s review, which denounced “The Night Porter” as a “vile attempt to excite us through reminiscences of oppression and torment,” certainly highlights the controversial nature of the relationship portrayed between a former concentration camp guard and an inmate under his command.

40 years after its debut, I still find Liliana Cavini’s film, “The Night Porter,” a compelling exploration of complex themes. To some, it may appear repugnant or vile, but beneath the surface lies a broader critique of the Nazi regime. This critique encompasses hypocrisy, repressed homosexuality, and an examination of the corruption and desperation that comes with power. “The Night Porter” serves as a masterclass in examining relationships and cruelty through the lens of transgression, mirroring Nietzsche’s notion of gazing into the abyss, which he suggested stares back at us.

The Complex Roles of Master and Servant

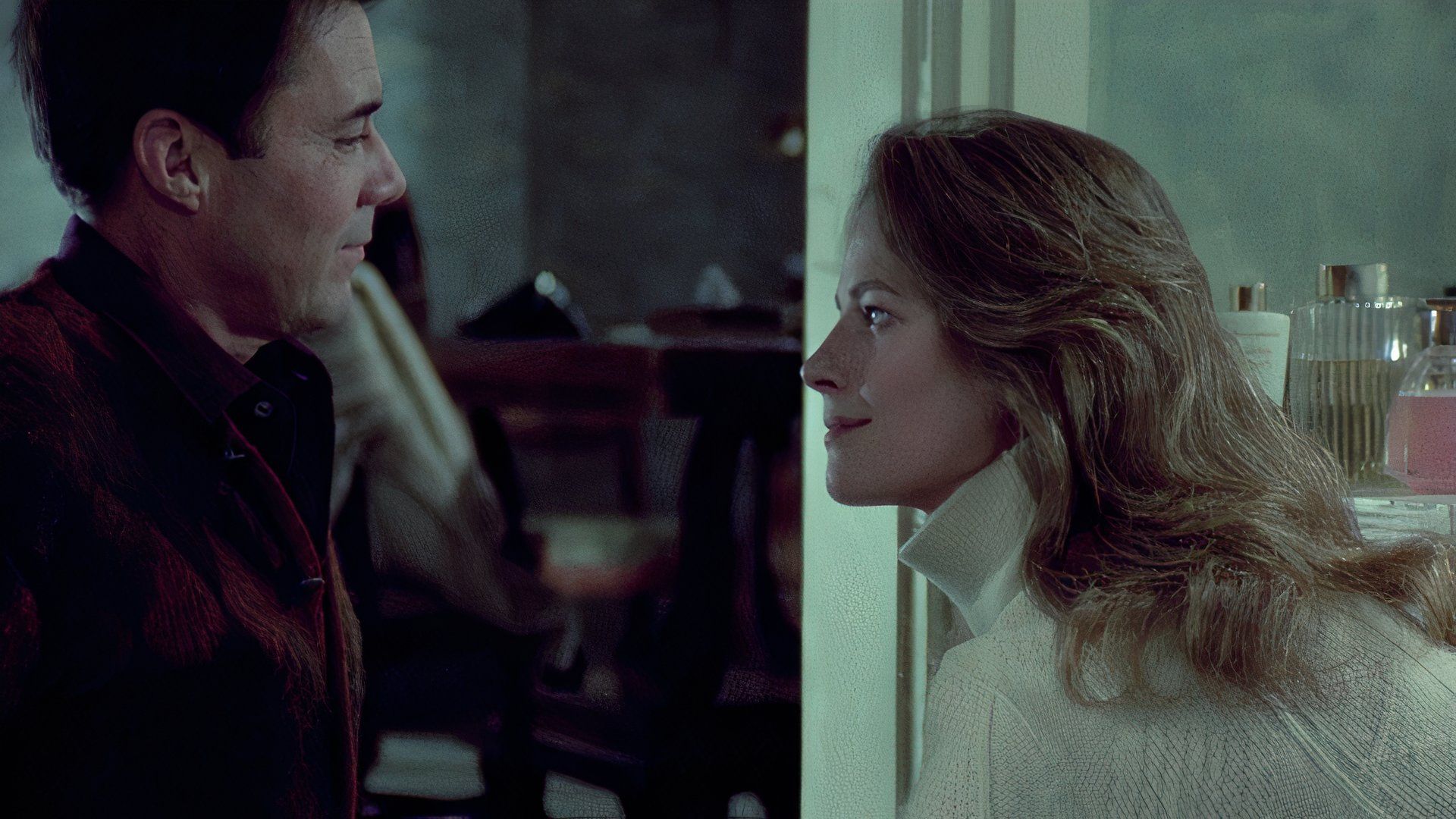

One day, Max (Dirk Bogarde), a man evading his past as a guard at a high-class Viennese hotel and formerly of the SS concentration camps, finds himself in an unusual situation. He yearns for a life as inconspicuous as a timid mouse in a church, detached from his tumultuous history. This solitude is momentarily disrupted when Lucia (Charlotte Rampling), a former camp inmate who had been under Max’s supervision, attends an opera performance one evening. From afar, they catch each other’s gaze, marking the beginning of a significant shift in their lives.

In this scene, Cavani cleverly uses flashbacks to reflect our connection with the movie as we witness it, where Max films Lucia closely while she waits in line for an inspection at a concentration camp. This intimate capture of Lucia’s vulnerability and Max assuming the filmmaker role emphasizes the sense of voyeurism that Cavani intends for the audience to experience.

The fundamental idea behind any sadomasochistic relationship involves two roles: the dominator (master) and the submissive (servant). This concept was initially presented by the Marquis de Sade through his characters Justine and Juliette. Essentially, it boils down to who endures the pain and who inflicts it. In scenes that show Max and Lucia in the concentration camp, it’s clear that Max assumes a dominant position, while Lucia takes on the submissive role.

In this movie, Max, previously a war criminal, finds himself in a position where he must face his past actions. This dynamic is flipped, as Max now faces potential prosecution if Lucia decides to betray him. The filmmaker, Cavani, presents these intricate roles, which some may find disturbing, but it’s not the first of its kind to delve into the complex bond between a former guard and prisoner who meet again after the war.

The Hypocrisy of the Nazi Regime

In 1963, the film “Passenger” was produced, although it wasn’t officially completed. This movie narrated a unique tale about a female former concentration camp guard who encountered a female passenger on a cruise ship. Similar to “The Night Porter,” “Passenger” incorporated flashbacks and palpable sexual tension, delving into the complex dynamic of master and servant. A point that Ebert may have missed in his review was how Cavani cleverly employed homoerotic undertones to highlight the hypocrisy within the Nazi regime.

Among Max’s war-time companions, there’s Bert (Amedeo Amodio), who amuses Max in his hotel room by dancing; Director Liliana Cavani employs flashback to depict this same dance taking place at the camp, with Bert donning a skimpy pair of briefs and heavy makeup. This continuity between ex-SS members finding pleasure in similar suggestive performances in their present lives as they did when they held power, serves as a stark illustration of the hypocrisy in the regime’s stance towards homosexuality. Upon The Night Porter’s release by The Criterion Collection, an interview with Cavani further reinforced this idea, with her asserting that she viewed the SS as merely “a creation of a choreographer.

Integrating Subtlety and Subversion

The explicit sexual themes found in “The Night Porter” are undeniably prominent and offer a stark portrayal of sadomasochism and the dynamics shaped by power. Yet, beneath this overt content, the film also delves deep into various aspects of the Nazi era, unveiling their glaring hypocrisy.

The ex-members of the SS and their persistent efforts to maintain their role as the false Pretorian guard of the Nazi government are not only shown through their ongoing fellowship with each other, but also by a secondary character, Countess Erika Stein (portrayed by Ira Miranda). This countess, although appearing weakened and powerless, symbolically represents Erika, a well-known marching song sung by the SS. Interestingly, this tune appears in two other films related to the Nazi regime: “Uprising” and “Schindler’s List.

In the movie “The Night Porter“, there’s no other moment that encapsulates its essence quite like the one featuring Lucia singing “If I Could Wish for Something” in a nightclub, a melancholic tune expressing yearning for nostalgia. This scene is often mistakenly viewed as mere titillation due to its sexual content. However, much like other parts of the film, this scene too functions subtly to expose the hypocrisy inherent in Nazism.

As a fervent admirer, I find it profoundly ironic and revealing of their contradictory beliefs, that some Nazi individuals are currently appreciating Friedrich Hollaender’s music in an open setting. This is because, as history tells us, many works from Jewish writers, artists, and intellectuals like Hollaender were ruthlessly suppressed during the early years of the Nazi regime. Such instances underscore the hypocrisy inherent in their ideology.

A Look Into the Darker Side of Humanity

The argument that “The Night Porter” deliberately tries to arouse and be sexually graphic reinforces the idea that its message is often misconstrued, as when sexuality is stripped of its sensual connotations, it transforms into an exploration of power dynamics, much like Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work in Salo or the 120 Days of Sodom. However, this didn’t deter other films such as “The Gestapo’s Last Orgy” and “Deported Women of the SS Special Section,” and others in the Nazi-exploitation genre from emulating this style with the aim of generating shock value.

Despite being a contentious film, there’s no denying that The Night Porter is a powerfully crafted work of transgressive art. It offers a unique perspective on Stockholm syndrome, power dynamics, subjugation, and the roles individuals play under an authoritarian regime. Art that provokes thought and stirs emotions among its viewers holds significant value in our shared human journey.

One key insight gleaned from the acting of Charlotte Rampling and Dirk Bogarde is that the traditional roles such as master and servant, dominance and submission often lack clear boundaries as we might initially perceive. Their performances suggest that transgressive art, which we engage with, should always be subject to various interpretations and analysis.

Read More

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Box Office: ‘Jurassic World Rebirth’ Stomping to $127M U.S. Bow, North of $250M Million Globally

- Silver Rate Forecast

- “Golden” Moment: How ‘KPop Demon Hunters’ Created the Year’s Catchiest Soundtrack

- Castle Duels tier list – Best Legendary and Epic cards

- Black Myth: Wukong minimum & recommended system requirements for PC

- Mech Vs Aliens codes – Currently active promos (June 2025)

2024-10-04 03:31