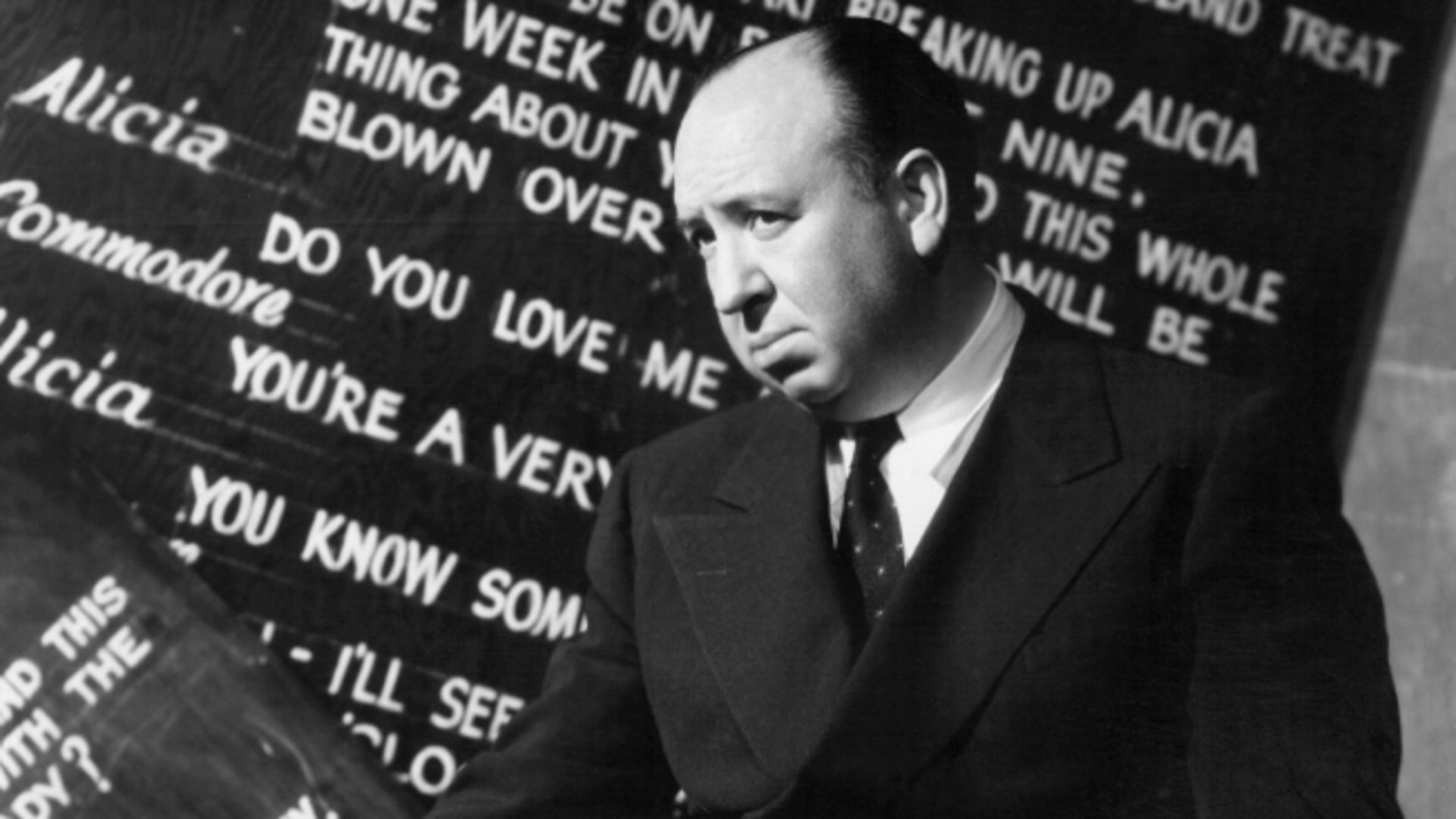

As a seasoned film historian and connoisseur of all things Hitchcockian, I find myself utterly captivated by the tale of Alfred Hitchcock‘s audacious foray into the realm of nuclear secrets during the making of “Notorious.” The man was nothing if not daring, always pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable, and often teetering on the brink of scandal.

Warning: This article contains major spoilers for the 1946 movie, Notorious.

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Notorious” could be considered the initial work in the post-war Nazi political thriller category, though this wasn’t necessarily planned. Imagine it as an unusual twin piece to the story of Oppenheimer you’ve never come across before. The timing was perfect for RKO Radio Pictures in 1946. With the war over, this film depicted former Nazis executing a revenge terrorist act, providing a chilling reflection of contemporary events.

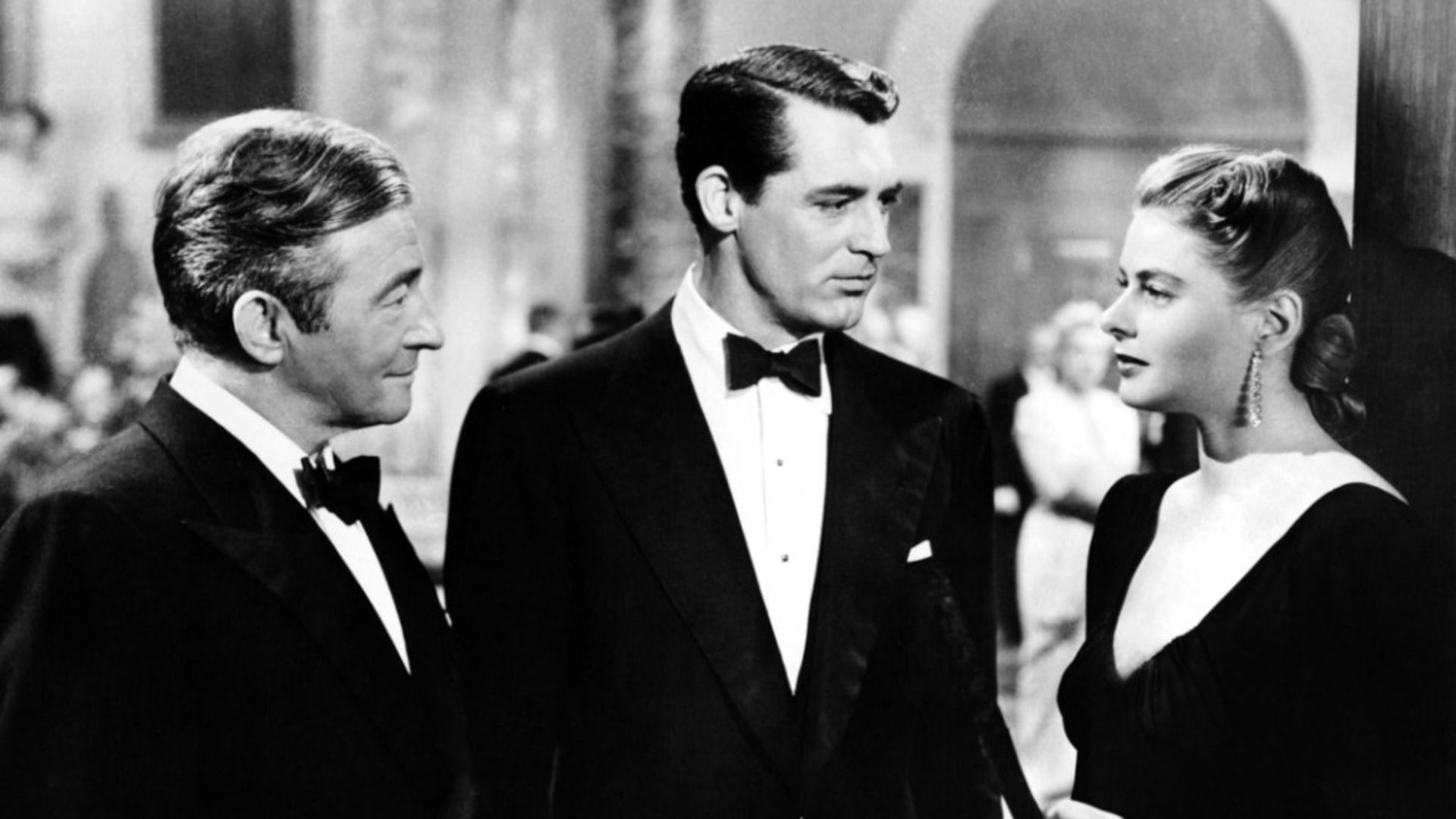

Featuring Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman, “Notorious” is often hailed as one of Alfred Hitchcock’s best works. Made during his early days in America, the film benefited from the support of RKO studio head David O. Selznick and writer Ben Hecht. The cast and crew were indeed star-studded, but countless others played crucial roles behind the scenes in bringing this movie to life. Interestingly, you won’t find any scientists credited in the film.

This story features many classic elements reminiscent of Hitchcock’s style: characters living under the shadow of domineering mothers, a complex plot twist that plays a crucial role (though subtler than the illogical missing handrail in Vertigo), an unexpected ending, and a brief appearance by the director himself. However, unlike Hitchcock, this tale tackles a grave subject matter with an ironic undertone – a man exploiting his lover, coercing a recovering alcoholic to gain access to a secure wine cellar, which seems almost mocking given her past struggles.

In many of his films, the finer points were more like decorations, taking a backseat to the interactions between characters, the storylines, visual elements, and overall themes. The filmmakers left it up to viewers to imagine some details, such as the outcome of the main antagonist, which was never disclosed. When it came to specifics, Hecht and Hitchcock were sparse with their explanations, a decision likely driven by the fact that they knew too much about the story’s intricacies.

In this hypothetical scenario where Robert Oppenheimer’s weapon of mass destruction, the A-bomb, wasn’t fully complete by 1946, Alfred Hitchcock’s film “Trinity” might have raised some uncomfortable questions about an English immigrant and RKO. The film could potentially be delayed or edited to avoid alerting the Axis powers, requiring reshoots. To Hitchcock, the A-bomb was simply a plot device for his new romantic espionage flick, regardless of its potential national security implications. In essence, a MacGuffin, a breach of national security, they were all the same thing in his eyes.

The Manhattan Project Goes Hollywood

During the breakout of World War II, there was an explosion in the production of simple, patriotic films. Even with the constraints set, Alfred Hitchcock maintained his high standard of work. However, it’s worth noting that these productions often leaned towards one-dimensional anti-German narratives. In quick succession, he directed Saboteur, Lifeboat, and Foreign Correspondent, all under the direction of his producer, Selznick. While Hitchcock contributed some ideas, most of the scriptwriting was done by Ben Hecht, who had already garnered two Academy Awards at that time.

In the film “Notorious,” Grant assumes the role of a skeptical federal agent who compels an alcoholic woman, the daughter of a German spy, played by Ingrid Bergman, to secretly work for the U.S. in Rio de Janeiro. Her mission is to infiltrate the inner circle of her smitten adversary, portrayed by Claude Rains. As the narrative unfolds, she finds herself caught in a romantic dilemma involving Rains’ character. Interestingly, Rains gives his villainous persona more depth than usual for a Hitchcock antagonist, making the characters feel versatile enough to fit into various settings or conflicts with only minor adjustments. This is particularly impressive given the film’s thin plotline. Moreover, the type of uranium used in the story was chosen at random by Hitchcock because he had an affinity for vintage wines.

Set following the war and initially conceptualized before Europe’s conflict ended, Notorious portrays a purely fictional account of German sympathizers living in exile seeking retribution for the Third Reich. The storyline revolves around a nuclear bomb project constructed by former Nazis in South America, which remains to be unveiled. This plot seems less far-fetched when considering it was conceived amidst the war, before Germany’s war machinery had been completely destroyed and they were still attempting to develop their own nuclear program. The narrative underwent changes when the setting was shifted to 1946 instead of April 1945 during production. To maintain secrecy around the most clandestine operation of WWII, the director received no assistance from government advisors or consultants.

How a Foreign National Obtained Inside Information

As a devoted admirer, let me share an intriguing tidbit I uncovered about the legendary Alfred Hitchcock. In his expansive network, he had a friend named Russell Maloney, a reporter for The New Yorker. Instead of letting juicy rumors vanish into the void or be deemed unprintable, Maloney chose to confide in Hitchcock about a secret location in the western United States, under military protection by the US Army.

When I brought up the topic with Selznick, he reacted puzzled and asked, ‘What do you mean by Uranium?’ I clarified, ‘It’s Uranium-235.’ He seemed perplexed again. I explained, ‘It’s what they plan to use for the atom bomb.’ He appeared confused once more and questioned, ‘What bomb are you talking about?’ I replied patiently, ‘Everyone knows about this. The Germans are attempting to produce heavy water in Norway; this is its purpose.’ He then expressed his skepticism, stating, ‘I believe this is the most absurd concept for a movie.’ I conceded, ‘Alright, if you’re not fond of Uranium, let’s change the focus to industrial diamonds or jewelry—whatever suits you better. I don’t mind.’

It’s worth noting that only a select group of experts, academics, and government personnel understood the concept of an atom in 1945, including complex ideas such as an atom bomb or a “chain reaction”. Inquisitiveness led him and Hecht to visit a Cal Tech classroom for research. They had a tense conversation with physicist Robert A. Millikan who strongly disputed the possibility of an atomic bomb. The Brit in question was then quickly reported, which Hitchcock found amusing as he later revealed he was under FBI surveillance for the following three months.

In Selznick’s judgment, his intuition was on point, yet Hitchcock’s persistence in maintaining the uranium angle proved more accurate. This is because the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki took place prior to the release of the film Notorious, during its production. It made perfect sense for a director like Hitchcock, who was seeking current material for his spy story. Remarkably, he employed scientific terminology as the pivotal “MacGuffin,” a term coined by Alfred Hitchcock himself to describe an object that motivates the characters but holds little interest for the audience. In essence, what could have been a more fitting plot device for a movie about espionage than a subject shrouded in secrecy by the US government?

Could Hitchcock Have Been Tried for Revealing State Secrets?

Was what happened in this situation legal? Well, it was somewhat of a gray area. The individual managed to evade an FBI visit due to the extended production period that allowed the bombs to be used publicly before the film’s release in 1946. Unlike others who leaked information about the A-bomb like Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, Hecht and Hitchcock only hinted at the program rather than revealing specific details about fission. He managed to avoid deportation, but he was certainly under surveillance during pre-production. He didn’t seem to take his movie plans too seriously or maybe even found them amusing since he didn’t make much effort to hide them.

As a film enthusiast, I’ve often pondered that perhaps I was more privy to certain secrets than some government officials during my time. It’s speculated that the idea of an atomic bomb had been in circulation for over a decade, and it’s likely that even Churchill was privy to these research findings. Yet, it seems I, Alfred Hitchcock, was better informed than many within both the American and British administrations about the construction of the ultimate weapon – the bomb-to-end-all-bombs – in the arid expanse of the desert.

As a passionate film buff, I found myself perplexed by the cryptic discussions about mineral ores in our script, as it wasn’t evident to me or the producers whether this detail would resonate with an average moviegoer before August 1945. Uranium’s role as a weapon was not widely known at that time, and I felt it essential to clarify or adjust the plot for the sake of our audience.

Read More

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Silver Rate Forecast

- USD MXN PREDICTION

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- Pi Network (PI) Price Prediction for 2025

- How to Watch 2025 NBA Draft Live Online Without Cable

- Castle Duels tier list – Best Legendary and Epic cards

2024-09-23 06:31