When movie makers transform literature into films, even minor alterations can significantly affect a story’s emotional depth and influence. Consequently, adaptations often face close examination from fans, critics, and occasionally the authors themselves. This scrutiny is particularly intense when the book was penned by a renowned Pulitzer Prize winner like Cormac McCarthy. In 2007, Joel and Ethan Coen, acclaimed filmmakers, adapted McCarthy’s “No Country for Old Men,” which garnered widespread critical praise and was lauded for its adherence to the original’s atmosphere and plotline.

One noteworthy, yet poignantly somber scene in the movie – Carla Jean Moss’s last, decisive encounter with the antagonist Anton Chigurh – undergoes a subtle transformation compared to Cormac McCarthy’s original text. In this adaptation, Carla Jean’s reaction shifts from a desperate, heartfelt plea on paper to a weary, almost defiant submission on screen. Despite seemingly deviating from the novel’s essence, this change could be interpreted as reinforcing the tragic heart of the story. It serves to make her ending all the more touching and poignant, providing a profound commentary on futility, destiny, and the true meaning of courage in a ruthless, indifferent universe – a theme that harmoniously reflects the Coen brothers’ unique cinematic perspective.

McCarthy’s Carla Jean Was Gripped With Grief & Fear

Before delving into Carla Jean Moss’s heartbreaking final scene and its literary roots, let’s remember the harrowing odyssey that leads her to the critical event depicted in Coen Brothers’ film adaptation of “No Country for Old Men.” Although the movie is intense from Javier Bardem’s introduction with his eerie gaze and peculiar hairstyle, it intensifies when Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a welder on an antelope hunt, discovers the gruesome remnants of a botched drug deal in the arid Texas desert. His life takes a dramatic turn when he picks up a suitcase containing two million dollars. This action swiftly puts him under the watchful eye of numerous dangerous individuals, most ominously the relentless, seemingly supernatural assassin, Anton Chigurh, who is tasked with retrieving the money.

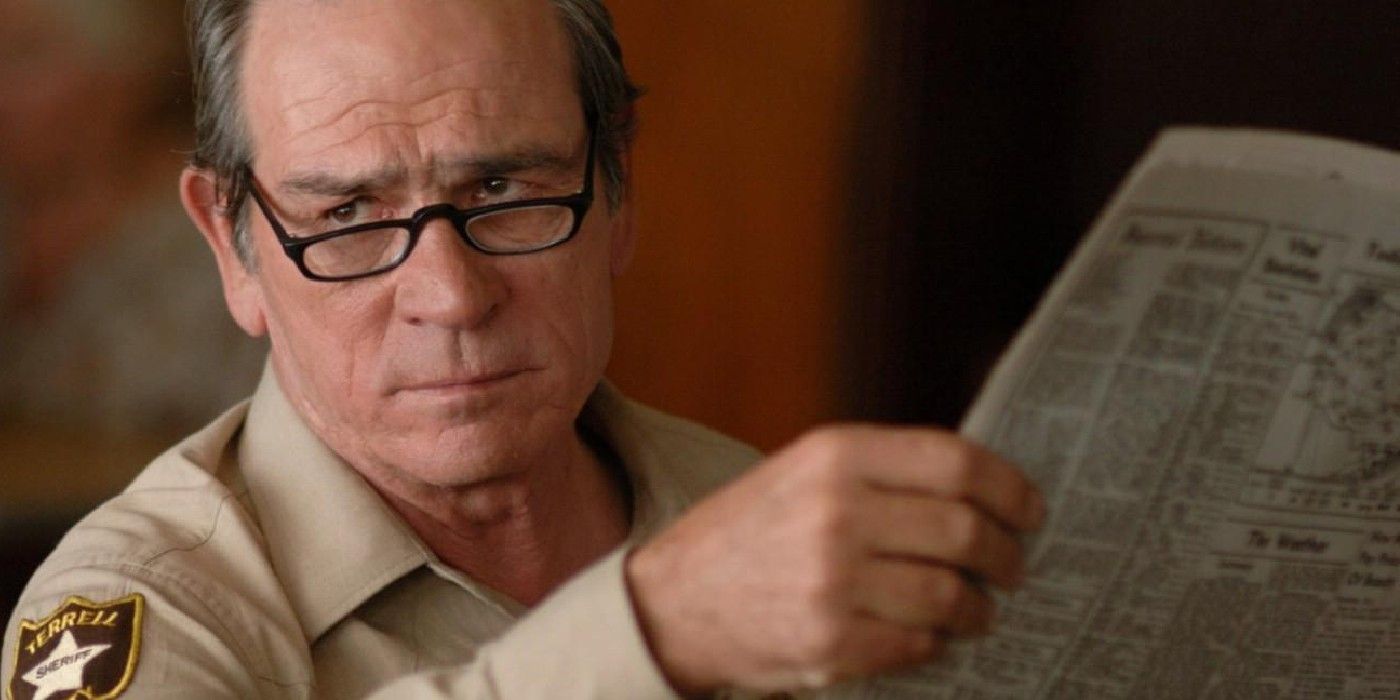

In the grim investigation led by Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), the path of chaos left by the enigmatic character Chigurh becomes clearer. Fearing for his life, Moss sends his wife Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald) to a safe place as he tries to escape from his pursuers. Unfortunately, despite Moss’s cunning efforts, he is eventually found and meets his end, not at the hands of Chigurh but by members of the Mexican cartel. However, driven by his twisted sense of “principle,” Chigurh still feels that his dealings with the Moss family are incomplete. Eventually, he locates Carla Jean, after she attends her mother’s funeral and returns to her deceased mother’s house, for a final confrontation tied to Llewelyn’s earlier decisions and a promise Chigurh had made.

In the movie adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s book, the interaction between Chigurh and Carla Jean unfolds differently. While in the novel, Carla Jean is depicted as a woman overwhelmed by grief and fear, pleading for her life, in the film, Carla Jean attempts to reason with Chigurh, showing raw emotional vulnerability through sobbing and shaking her head. This change from the book highlights how the film deviates in portraying this critical confrontation.

In this depiction, Carla Jean’s humanness is highlighted, showcasing her relatable longing for life and her struggle to comprehend or accept the ruthless reasoning of her executioner. She hangs onto the belief that pleas, tears, or entreaties could sway the unyielding, thus making her ultimate fate a poignant example of innocence squashed by merciless wickedness. In the last moments of McCarthy’s character, Carla Jean embodies raw, undiluted human suffering.

The Film Shows a Quiet Acceptance of Fate Through Carla Jean

The Coens Bring a Cinematic Shift With Their Alteration

In their film version, the Coen Brothers set up this critical meeting with a spine-tingling ambiance. The viewers already know that Chigurh is after Moss’ wife, as hinted by Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson), and following a Mexican mob killing Moss, the tension gradually escalates towards Carla Jean. Thus, when the scene finally unfolds, it does so with maximum impact. The interaction between Carla Jean and Chigurh takes place with sparse dialogue, frequently interrupted by long pauses, under the dim lighting of Carla Jean’s mother’s house, generating an eerie sense of anticipation.

In the intriguing scene where Anton Chigurh displays his coin, presenting me with the same choice he offered others, my character Carla Jean’s reaction in the movie significantly diverges from her literary counterpart. Unlike the book version of Carla, who after a brief struggle succumbs to fear and calls the coin “heads,” I remain resolute, exhibiting neither pleading nor an emotional collapse in the film adaptation. As the actress who brought Carla Jean to life on screen, I experienced this unique portrayal firsthand.

In this scene, when Carla Jean notices Chigurh seated, she admits, “I don’t have the money, what little I had is spent already, and there are still many bills to pay. Today was my mother’s burial, and her funeral expenses remain unpaid.” In response, Chigurh remains unfazed, saying, “I don’t worry about it.” Carla Jean then requests, “I need to sit down,” indicating that she has resigned herself to the realization that destiny has caught up with her, leaving few options for resistance.

In a weary manner that hinted at deep sorrow and a keen awareness of the world’s harshness, Carla Jean declined to participate in Chigurh’s coin toss. Her quiet yet forceful statement, “The coin doesn’t hold any power. It’s just you,” was a remarkable act of rebellion. She refused to be swayed by Chigurh’s distorted game of fate, which some view as a symbol of Death, given his ominous attire and captive bolt pistol. This supposed “respite” offered by the system was rejected by her.

As I chose not to engage, I stripped him of the pleasure of seeing his capricious authority impact my destiny. The silence, the intense focus on McDonald’s emotive face, brimming with a world of sorrow and acceptance, contrasted with Bardem’s chilling tranquility — transformed the atmosphere from one of frantic dread to one that felt almost philosophical, like a confrontation of existential proportions.

The Emotional Weight of Change in No Country for Old Men Hurts Even More

In this revised portrayal by the Coens, Carla Jean’s character gains added depth, making her tragic fate even more poignant within their cinematic world. Kathy Bates’ portrayal of Carla Jean’s raw anguish is deeply relatable and sad. However, the Coens’ interpretation, highlighting her defiance against Chigurh’s “game,” gives her character a powerful final moment. As viewers, we find ourselves secretly hoping for Carla Jean’s survival, but she meets her end. Yet, her defiance in the face of an unyielding, seemingly primal force of destruction, offers a glimmer of agency, making her story all the more moving.

In a temporary setback, Chigurh, whose actions are frequently associated with the unpredictability of a coin flip, is momentarily disarmed. Instead of allowing him to mask his violence through random chance, Carla Jean compels him to act directly without any deception. Refusing to play by Chigurh’s rules results in immediate defeat for anyone else, but here, Carla Jean’s defiance transcends those rules, suggesting that her death was a result of Chigurh’s intentional actions rather than mere fate. This understated courage serves to highlight the film’s recurring themes of destiny, inexorability, and moral decay. Throughout the movie, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) struggles with a world that seems foreign to him, expressing feelings of being “outmatched” by the emergence of a new breed of violence. He yearns for the straightforward morality stories of the past, but as his cousin Ellis points out, referencing their own violent family history, “What you’re dealing with isn’t anything new… You can’t halt what’s approaching.

In my perspective, when Carla Jean bravely challenges Chigurh, it’s a poignant demonstration of her acceptance that she has nothing left to lose. This isn’t bravery born from hope for survival, but rather the determination to control her fate even as it seems inevitable. This theme echoes the Coens’ frequent portrayal of characters grappling with unjust, cruel circumstances, such as Larry Gopnik in A Serious Man or Marge Gunderson confronting senseless wrongdoing in Fargo.

In their storytelling, the Coen Brothers create a narrative that invites viewers to imagine events unfolding, such as when Chigurh leaves Carla Jean’s house and examines his boots for blood. This suggests her unseen murder taking place in the minds of the audience, a more chilling approach than showing it directly. The fact that Carla Jean remains strong and silent after these events creates an even heavier silence, making her loss all the more poignant. To this day, over 18 years since its release, this scene, much like the film itself, demonstrates the power of subtlety – sometimes less can have a profound impact.

Read More

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Silver Rate Forecast

- USD MXN PREDICTION

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

- Grimguard Tactics tier list – Ranking the main classes

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Pi Network (PI) Price Prediction for 2025

- Castle Duels tier list – Best Legendary and Epic cards

- How to Watch 2025 NBA Draft Live Online Without Cable

2025-05-31 06:08