As I delve into the captivating tale of Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, two extraordinary individuals who defied conventions and created timeless cinema, I am deeply moved by their resilience and tenacity. Their journey, marked by love, collaboration, and a shared passion for art, is an inspiring testament to the power of human connections.

It might seem logical to presume that Merchant Ivory, the esteemed production company known for producing timeless costume dramas like “The Remains of the Day” and “A Room with a View,” would operate effortlessly as a sophisticated filmmaking powerhouse. However, according to director Stephen Soucy in his enlightening documentary, “Merchant Ivory,” producers Ismail Merchant and James Ivory frequently faced such severe limitations that Anthony Hopkins even filed a lawsuit against the company for unpaid wages.

Soucy’s documentary is brimming with revealing insights about the pair, yet it also stirs emotions when it chronicles the unique relationship between Ivory, an Oregon native, and Merchant, a Muslim born in Mumbai. As a gay couple during a challenging period for such relationships, they faced numerous cultural hurdles and episodes of infidelity. However, their personal bond and professional partnership, which led to 43 films and more than two dozen Oscar nominations, proved to be indestructible.

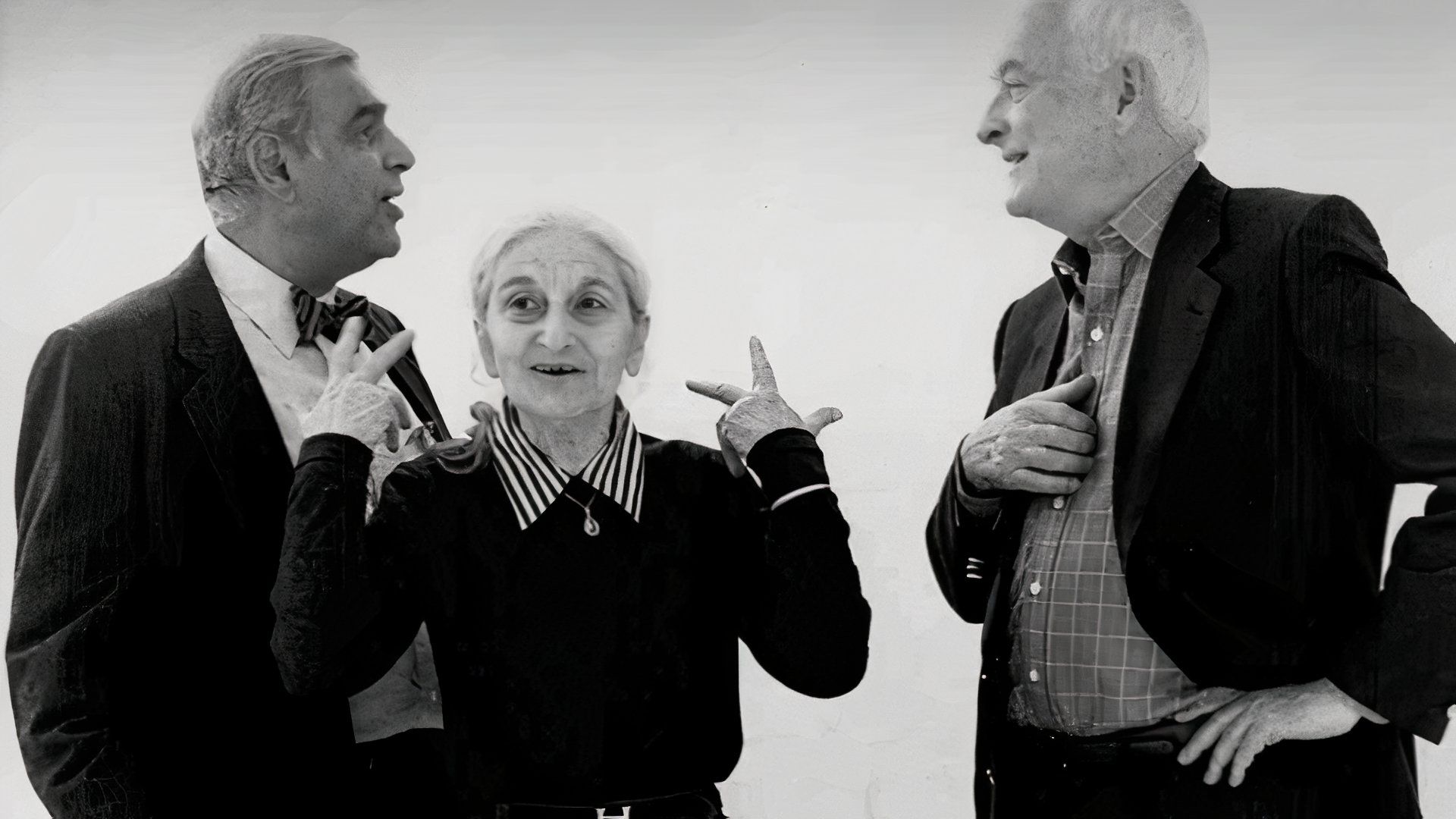

In sharing the company’s narrative, Soucy secures fresh conversations with long-time members of Merchant Ivory such as Emma Thompson, Helena Bonham Carter, Vanessa Redgrave, and Hugh Grant. However, Ivory himself stands out as the most vital interviewee, at 96 years old and still working. He elevates this documentary to a must-watch for those eager for additional insights into a personal and professional bond that was as captivating as any Merchant Ivory production.

The Meager Beginnings of an Oscar-Nominated Duo

The thrifty attitude of Merchant Ivory films, particularly in their initial phase, contributes significantly to the comedy and unexpected elements found in Soucy’s documentary. Much of this can be attributed to Merchant, as described by Hugh Grant, who was “unconventional” as a producer, a claim that Soucy provides ample proof of. Ivory, however, put faith in Merchant to “tie everything together,” which he managed to do, frequently in inventive ways.

The merchant was famed for deterring dissatisfied team members from leaving a project by organizing unique, once-in-a-lifetime excursions. In one instance, when representatives sent messages to their clients instructing them to halt work on a Merchant Ivory production due to unpaid wages, the merchant secretly intercepted these messages before they reached their hotel rooms, allowing filming to carry on. According to Anna Kythreotis, who ghostwrote for Merchant, “You always sought ways to get rid of him at night, but you couldn’t help but adore him.”

Love is the recurring theme in Soucy’s documentary, present both on-screen and off. Two of Merchant Ivory’s most compelling films delved into love, one hidden beneath the weight of responsibility (The Remains of the Day) and another love that was frequently suppressed, often under the threat of imprisonment. This latter theme is poignantly depicted in a powerful sequence from their pioneering 1987 same-sex romance, Maurice. This film represented Merchant Ivory’s daring continuation after A Room with a View, which had garnered three Oscars but failed to generate significant financial success for the company.

Even though, Maurice was a movie that Ismail Merchant (Ivory being his creative partner) was determined to produce during a period when then-British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher criticized the idea that children have an inherent right to be homosexual. In this context, Maurice is referred to as the pioneer or forerunner of gay cinema, playing a significant role in launching Hugh Grant’s acting career.

For Merchant and Ivory, It Was “Love at Second Sight”

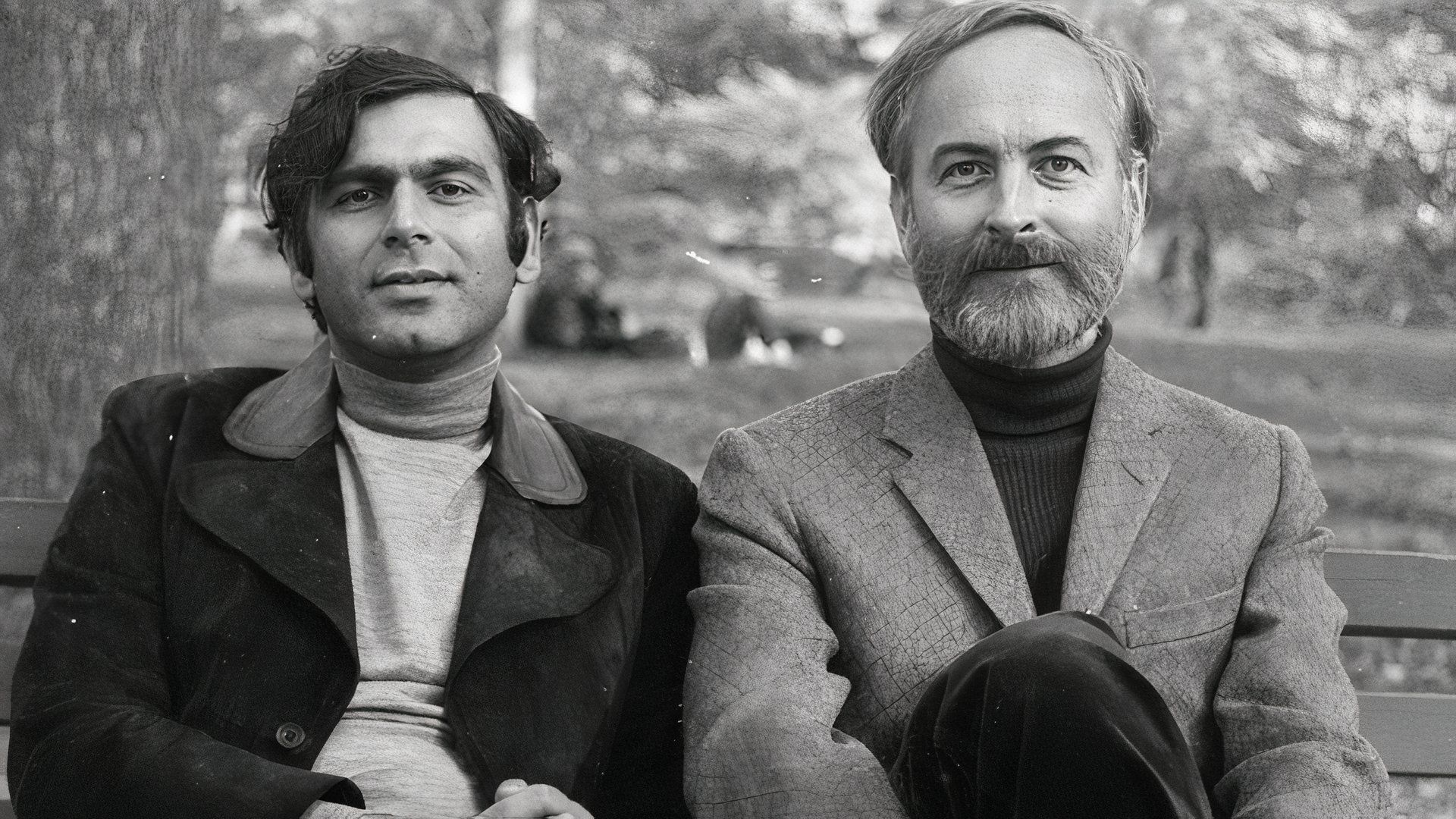

Ivory speaks with a hint of British reserve as he shares the highs and lows of his 40-year-long friendship with Merchant. We discover that they first crossed paths at the Indian Consulate in New York City during a screening of Ivory’s short film, “The Sword and the Flute,” in 1961. He describes their encounter as “love at second sight.” They quickly formed not only a personal bond but also a professional partnership in filmmaking, leaving for India to create English-language films tailored for the local market.

The couple kept their affection private. To the traditional Muslim family of Merchant, Ivory was merely his “American friend,” but to the observant cast of their debut film, a 1963 Indian drama titled The Householder, they were known as Jack and Jill.

In this movie titled “The Householder“, the music was created by composer Richard Robbins, who went on to pen tunes for a total of 21 films produced by Merchant Ivory. Interestingly, one of the film’s most shocking revelations is that Robbins had an affair with Merchant, as admitted by Ivory himself. The storyline of “The Householder” was adapted from the novel by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who later became a significant collaborator for the duo. Over her career, she wrote 23 screenplays for Merchant Ivory productions, including the 1979 film adaptation of Henry James’s novel “The Europeans“, which marked their first production outside India and significantly shifted their focus towards creating deeply emotional and highly literate adaptations of books.

Ivory Scores an Oscar for Call Me by Your Name

Soucy’s minimalistic and plain storytelling can be a drawback, but he, along with editor Jon Hart, manage to keep the pace engaging. They are not afraid to delve into how the quality of Merchant Ivory films started to decline when American studio funds became involved. Soucy skillfully extracts insightful comments from interviewees who hold fond memories of the duo. Sam Waterston (a three-time collaborator with Merchant Ivory) describes them as “fascinating pirates,” while Jhabvala’s daughter, with a mischievous grin, labels them “crooks and thieves.”

Indeed, Soucy’s intriguing documentary clearly shows that Ismail Merchant and James Ivory were an unusual partnership, to say the least; one a shrewd, cost-conscious producer always looking for ways to save money, while the other was a refined director dedicated to making enduring films and maintaining a lasting relationship. It’s worth noting that only Ivory remains among the original quartet of the company – Merchant passed away following abdominal surgery in 2005, and both Robbins and Jhabvala followed suit in 2012 and 2013 respectively. However, far from retiring, Ivory continues to be active in the industry.

In 2018, Ivory emerged as the oldest individual to receive an Oscar, triumphing with the Best Adapted Screenplay accolade for the film Call Me By Your Name. Reminiscent of Soucy’s documentary, this victory was a deserved and fitting finale for a man whose life and artistic endeavors have consistently tested limits.

Read More

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- USD MXN PREDICTION

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Pi Network (PI) Price Prediction for 2025

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Brent Oil Forecast

- How to Watch 2025 NBA Draft Live Online Without Cable

- Gold Rate Forecast

- USD JPY PREDICTION

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

2024-08-29 18:01