1929. A young man from the vibrant city of New York steps into a new era with a heart full of dreams and a mind brimming with ideas. The Roaring Twenties have just begun, and he’s eager to make his mark on this world that seems to be bursting at the seams with possibilities. He’s only 25, but his spirit is as old as time itself.

The music of the era resonates within him like a symphony, each note echoing his own hopes and fears. From the soulful croonings of Louis Armstrong to the upbeat rhythms of George Gershwin, he feels connected to these artists in ways he can’t quite put into words. He yearns for the day when he too can create music that moves people as deeply as theirs do.

He spends hours poring over books by authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, finding solace in their stories of love, loss, and the human condition. The Great Gatsby becomes a personal manifesto for him, a guiding light that illuminates his own path towards success.

He’s not just a listener or a reader; he’s an observer, taking mental notes of everything around him. From the bustling streets of New York to the glamorous parties held by the city’s elite, he soaks it all in, seeking inspiration for his own stories yet to be told.

As he walks through the city that never sleeps, he can’t help but feel a sense of excitement and anticipation. He knows that the Roaring Twenties are just the beginning, and he’s ready to seize every opportunity that comes his way.

And so, with dreams in his heart and a fire in his soul, our young man steps boldly into the unknown, eager to leave an indelible mark on the world of art, literature, and music. Little does he know that his name will one day become synonymous with the Golden Age of Hollywood – but for now, he’s just a starry-eyed dreamer, ready to take on the world.

Oh, and by the way, don’t worry about him too much; he’ll probably be just fine. After all, he’s got the whole wide world in his hands, and he’s not afraid to use them!

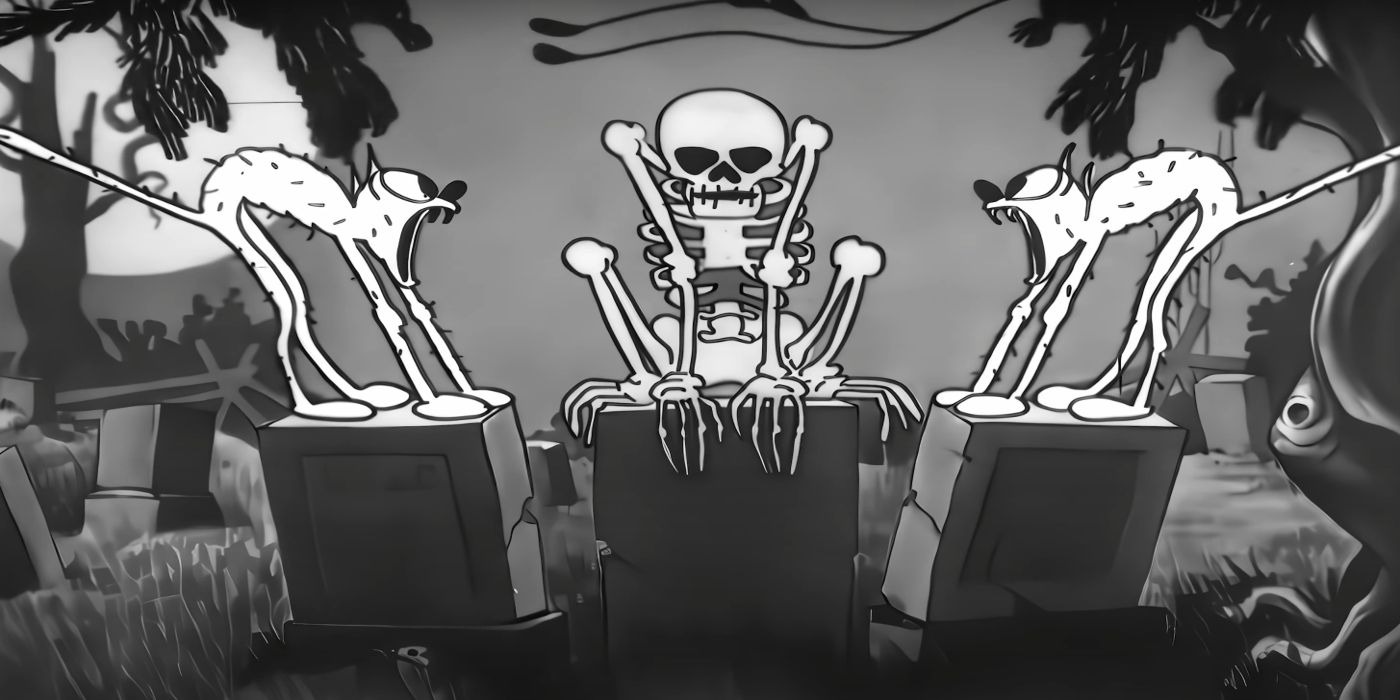

2025 marks a significant milestone for public domain as numerous iconic works across various mediums such as film, music, animation, literature, and more are set to be accessible to all. Last year’s Public Domain Day was particularly noteworthy with Disney’s Mickey Mouse making its debut entry. This year, we will see a multitude of Mickey Mouse animations joining the pool, along with other popular titles like Tintin, Popeye (time for Genndy Tartakovsky to get busy), “The Skeleton Dance” from Disney’s Silly Symphonies, as well as literary works such as William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway, and A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf. Notably, we can also look forward to the Marx Brothers’ first feature film, along with Alfred Hitchcock and John Ford’s initial sound films.

As a lifelong enthusiast of both literature and film, I can’t help but find the recent trend of adapting classic characters like Popeye and Tintin into horror films intriguing, albeit somewhat baffling. Having grown up with these beloved characters, it’s hard not to feel a sense of nostalgia and wonder at the prospect of seeing them in an entirely different light. However, as someone who values the preservation of artistic integrity, I can’t help but question whether this is a wise decision.

Fortunately, Duke University’s School of Law has come to the rescue with their informative video and write-up on works now considered free-to-use. As someone who often finds themselves navigating the complexities of copyright law, I can attest to the fact that this resource is a godsend for creators looking to tap into the vast pool of public domain works without fear of legal repercussions.

In any case, whether you’re a creator seeking inspiration or simply a fan eager to learn more about the history and significance of these classic works, I highly recommend taking a few moments to check out Duke University’s video and write-up. Trust me, it’s a BUNCH!

What Is Public Domain Day and What Even Is The Public Domain?

Hey there! You might be scratching your head thinking, “Why on earth am I being drawn into a copyright law discussion at this very moment?” But bear with me for a moment, won’t you?

While it’s easy to grumble about our current pop culture landscape dominated by sequels, reboots, and the like, it would be shortsighted not to acknowledge the benefits of utilizing pre-existing intellectual property. The fact is, these works offer a wealth of opportunities for new storytelling, which can enrich both culture and society.

History has a way of repeating itself (or at least rhyming), and art plays a crucial role in helping us understand that history. It provides lessons that can guide us through the present and future. In these trying times, we could all use a little more insight into ourselves and our world, and what better way to achieve that than through engaging with art?

So, let’s dive in, shall we? Not only will it be entertaining, but it may also shed some light on the world around us. After all, as movie critics, it’s our job to help you navigate the ever-evolving cinematic landscape!

As they put it on the Duke website:

At a time when many feel disheartened, questioning if our society’s challenges and differences are too deep-rooted for hope, Faulkner reminds us of “the timeless truths that give any narrative substance – love, honor, empathy, dignity, compassion, and selflessness.” Yet, contrary to these eternal principles, Faulkner’s work was neither fleeting nor doomed. Reiterating his own words, “The past is never completely gone; it isn’t even past.” This is the reason we should value the public domain.

OK, OK — Just Give Me A List Of Names I Should Care About

To clarify, it’s important to note that what you see here is merely a summary or selection. In actuality, there are many more names available for review, courtesy of the extensive records kept by the University of Pennsylvania’s Catalog of Copyright Entries.

BOOKS AND PLAYS

- William Faulkner, The Sound and the Fury

- Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms

- Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own

- Dashiell Hammett, Red Harvest and The Maltese Falcon (as serialized in Black Mask magazine)

- John Steinbeck, Cup of Gold (Steinbeck’s first novel)

- Richard Hughes, A High Wind in Jamaica

- Oliver La Farge, Laughing Boy: A Navajo Love Story

- Patrick Hamilton, Rope

- Arthur Wesley Wheen, the first English translation of All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque

- Agatha Christie, Seven Dials Mystery

- Robert Graves, Good-bye to All That

- E. B. White and James Thurber, Is Sex Necessary? Or, Why You Feel the Way You Do

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet (only the original German version, Briefe an einen jungen Dichter)

- Walter Lippmann, A Preface to Morals

- Ellery Queen (Frederic Dannay and Manfred Bennington Lee), The Roman Hat Mystery

FILMS

- A dozen more Mickey Mouse animations (including Mickey’s first talking appearance in The Karnival Kid)

- The Cocoanuts, directed by Robert Florey and Joseph Santley (the first Marx Brothers feature film)

- The Broadway Melody, directed by Harry Beaumont (winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture)

- The Hollywood Revue of 1929, directed by Charles Reisner (featuring the song “Singin’ in the Rain”)

- The Skeleton Dance, directed by Walt Disney and animated by Ub Iwerks (the first Silly Symphony short from Disney)

- Blackmail, directed by Alfred Hitchcock (Hitchcock’s first sound film)

- Hallelujah, directed by King Vidor (one of the first films from a major studio with an all-African-American cast)

- The Wild Party, directed by Dorothy Arzner (Clara Bow’s first “talkie”)

- Welcome Danger, directed by Clyde Bruckman and Malcolm St. Clair (the first full-sound comedy starring Harold Lloyd)

- On With the Show, directed by Alan Crosland (the first all-talking, all-color, feature-length film)

- Pandora’s Box (Die Büchse der Pandora), directed by G.W. Pabst

- Show Boat, directed by Harry A. Pollard (adaptation of the novel and musical)

- The Black Watch, directed by John Ford (Ford’s first sound film)

- Spite Marriage, directed by Edward Sedgwick and Buster Keaton (Keaton’s final silent feature)

- Say It with Songs, directed by Lloyd Bacon (follow-up to The Jazz Singer and The Singing Fool)

- Dynamite, directed by Cecil B. DeMille (DeMille’s first sound film)

- Gold Diggers of Broadway, directed Roy Del Ruth

CHARACTERS

- E. C. Segar, Popeye (in “Gobs of Work” from the Thimble Theatre comic strip)

- Hergé (Georges Remi), Tintin (in “Les Aventures de Tintin” from the magazine Le Petit Vingtième)

MUSICAL COMPOSITIONS AND SOUND RECORDINGS

- Singin’ in the Rain, lyrics by Arthur Freed, music by Nacio Herb Brown

- Ain’t Misbehavin’, lyrics by Andy Paul Razaf, music by Thomas W. “Fats” Waller & Harry Brooks (from the musical Hot Chocolates)

- An American in Paris, George Gershwin

- Boléro, Maurice Ravel

- (What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue, lyrics by Andy Paul Razaf, music by Thomas W. “Fats” Waller & Harry Brooks (a song about racial injustice from the musical Hot Chocolates)

- Tiptoe Through the Tulips, lyrics by Alfred Dubin, music by Joseph Burke

- Happy Days Are Here Again, lyrics by Jack Yellen, music by Milton Ager (the theme song for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign)

- What Is This Thing Called Love?, by Cole Porter (from Porter’s musical Wake Up and Dream)

- Am I Blue?, lyrics by Grant Clarke, music by Harry Akst

- You Were Meant for Me, lyrics by Arthur Freed, music by Nacio Herb Brown

- Honey, lyrics and music by Seymour Simons, Haven Gillespie, and Richard A. Whiting

- Waiting for a Train, lyrics and music by Jimmie Rodgers

- My Way’s Cloudy, recorded by Marian Anderson

- Rhapsody in Blue, recorded by George Gershwin

- Shreveport Stomp, recorded by Jelly Roll Morton

- Lazy, recorded by The Georgians

- Of All The Wrongs You Done To Me, recorded by Louis Armstrong and Clarence Williams’ Blue Five

- Deep Blue Sea Blues, recorded by Clara Smith

- The Gouge of Armour Avenue, recorded by Fletcher Henderson and his Orchestra featuring Big Charlie Green

- Mama’s Gone, Good Bye, recorded by Ray Miller and his Orchestra

- It Had To Be You, recorded by the Isham Jones Orchestra and by Marion Harris

- California Here I Come, recorded by Al Jolson

A big thank you goes out to the Duke Center for the Study of the Public Domain for gathering all this data into one place!

Read More

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- USD MXN PREDICTION

- Brent Oil Forecast

- USD JPY PREDICTION

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Pi Network (PI) Price Prediction for 2025

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Gold Rate Forecast

- How to Watch 2025 NBA Draft Live Online Without Cable

- Castle Duels tier list – Best Legendary and Epic cards

2024-12-31 05:34