Quick Links

- Germany, the Original Masters of Horror

- Why the Greatest German Film Was a Curse

- The Party Comes to an End

As a cinephile with a deep appreciation for the rich tapestry of cinematic history, I find myself utterly captivated by the tale of German Expressionism – a movement that burst onto the scene like a brilliant, chaotic firework, only to fizzle out far too soon.

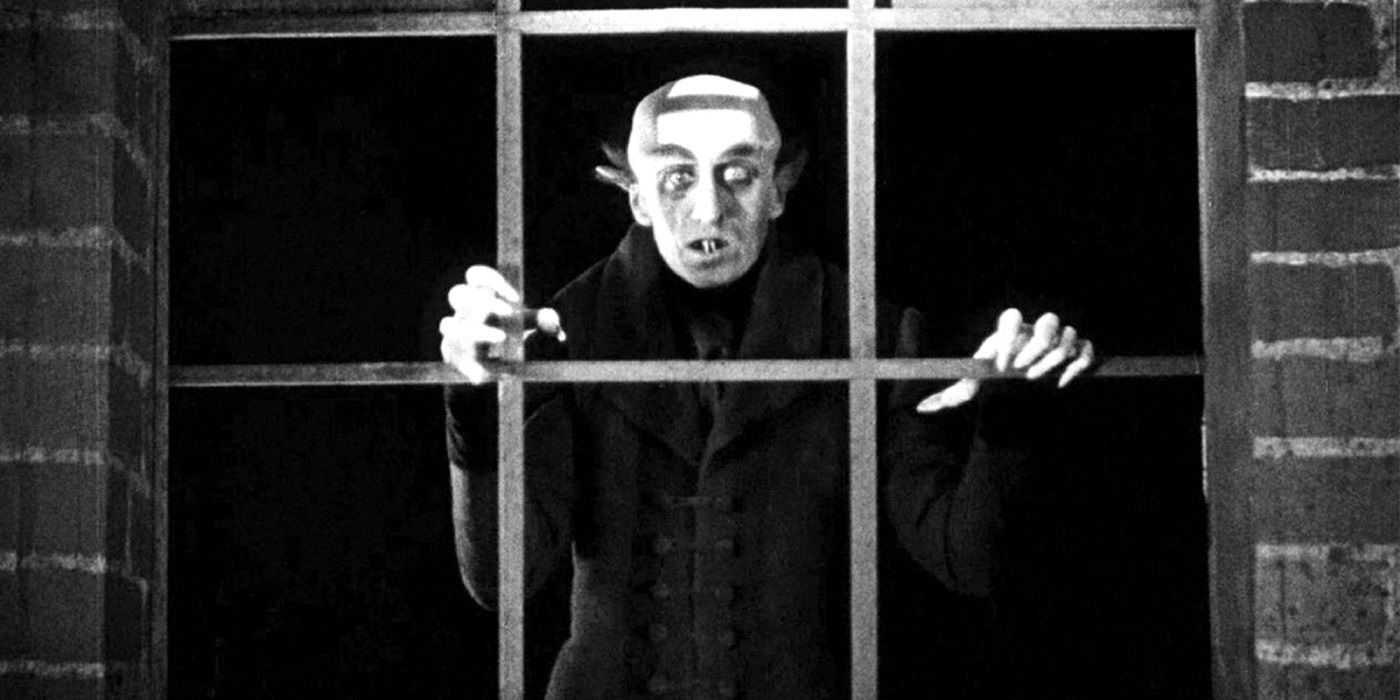

Currently screening in cinemas, Robert Eggers’ unique take on the vampire tale, Nosferatu, could very well be the most peculiar Christmas movie ever made. Beneath its sophisticated remake and IMAX presentation lies a complex and intriguing history that significantly influenced the art of filmmaking, and it’s not a pretty tale.

Struggling to balance personal creativity with financial needs, German filmmakers created awe-inspiring movies over a short span of time. Just like exceptional art often thrives under adversity, these films were shaped by significant challenges. They became renowned for dark tales exploring themes such as madness, greed, and self-destructive behavior.

One studio, UFA, held dominance among its peers, with its rise and fall mirroring the opulent yet tumultuous Weimar Republic. The two are inextricably linked, as UFA’s influence reached far beyond its heyday, shaping the early years of cinema as it sought to establish its identity. The artistic impact of these silent films is profound, even for contemporary viewers who haven’t seen them – elements from the brooding atmosphere of ‘Nosferatu’, the disillusionment and perversion in ‘M’, and the themes and art design of ‘Metropolis’ can be found in various modern genres such as Batman movies, noir films, and dystopian cinema to this day.

In the 1920s, the renowned British filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock received guidance from F.W. Murnau before he gained fame, and many Hollywood character actors had their beginnings in Berlin’s spotlight. Although the movement may have seemed to dwindle, it continued to thrive beneath the surface of movie culture.

Germany, the Original Masters of Horror

Robert Wiene’s 1920 movie, titled “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari“, is often recognized as the pioneering film during Germany’s Expressionist era, a groundbreaking piece that significantly boosted Germany’s reputation in cinema. To put it simply, this film could be seen as the initial manifestation, or the “patient zero”, of the wave of emotional intensity in films that came to be known as the “emo” movement.

Regardless of its peculiar style, this early film significantly shaped German cinema during the subsequent 15 years or so, with mixed results. Produced shortly after the devastating experience of World War I, it served as a poignant anti-war statement by its creators. Although the original subtext was altered, it eventually evolved into a surreal story about a hapless man, portrayed by Conrad Veidt, forced to kill against his will under the influence of a hypnotist. The deeper meaning behind this narrative was toned down, as suggested in “Modernism and Its Media”. According to historian Siegfried Kracauer, the director was pressured to conceal any potentially controversial messages to avoid controversy.

As per the perspective of pacifist thinker Janowitz, they crafted Cesare as a character representing an average person, who, due to the force of mandatory military duty, is trained to kill and be killed.

As a devoted admirer, I’d like to share some insights about an intriguing aspect of film history. In 1920, the profound message conveyed was a pressing warning, and it grew increasingly ominous in the following decades. Interestingly, most German films were primarily intended for international audiences rather than German citizens themselves. The films produced by UFA were often met with derision by German critics. Few Germans could afford cinema tickets, and the rampant inflation made exporting these films significantly more profitable.

As a cinephile reflecting on this timeless masterpiece, I can’t help but feel that a touch of modern production value could elevate its status even further. Enhancing it with striking special effects and authentic locations would only serve to breathe new life into this classic horror tale.

Why the Greatest German Film Was a Curse

Germany has produced an abundance of intellectually gifted individuals, and if you examine later films, you can trace the roots of German Expressionism. Roger Ebert referred to G.W. Pabst as the “master of psycho-sexual melodrama,” a title that anticipates dark romances such as ‘Blue Velvet’, ‘Mulholland Drive’, and ‘Fatal Attraction’. Originating from humble beginnings in the mid-’30s, Hollywood monster movies and film noir share a similar foundation rooted in the Gothic style.

In a surprising twist, American movies with larger budgets attempted to emulate the eerie charm of their German counterparts, which appeared as they did due to financial constraints. To mask their makeshift sets and poor lighting arrangements, the crews used stylistic backdrops and other creative strategies, manipulating light and shadow on shaky scenery. The result was a series of films that bore little resemblance to reality.

According to film historian Andrew Spicer, German Expressionism had a significant impact on a series of horror films produced by Universal Studios in the early 1930s. Since Universal was run by Carl Laemmle, who was born in Germany, they often employed talent from the Weimar era. In essence, the classic monster movies like Dracula (and its numerous remakes and sequels) can be traced back to F.W. Murnau’s unauthorized Nosferatu, a film that may have been banned but was not forgotten by German immigrants.

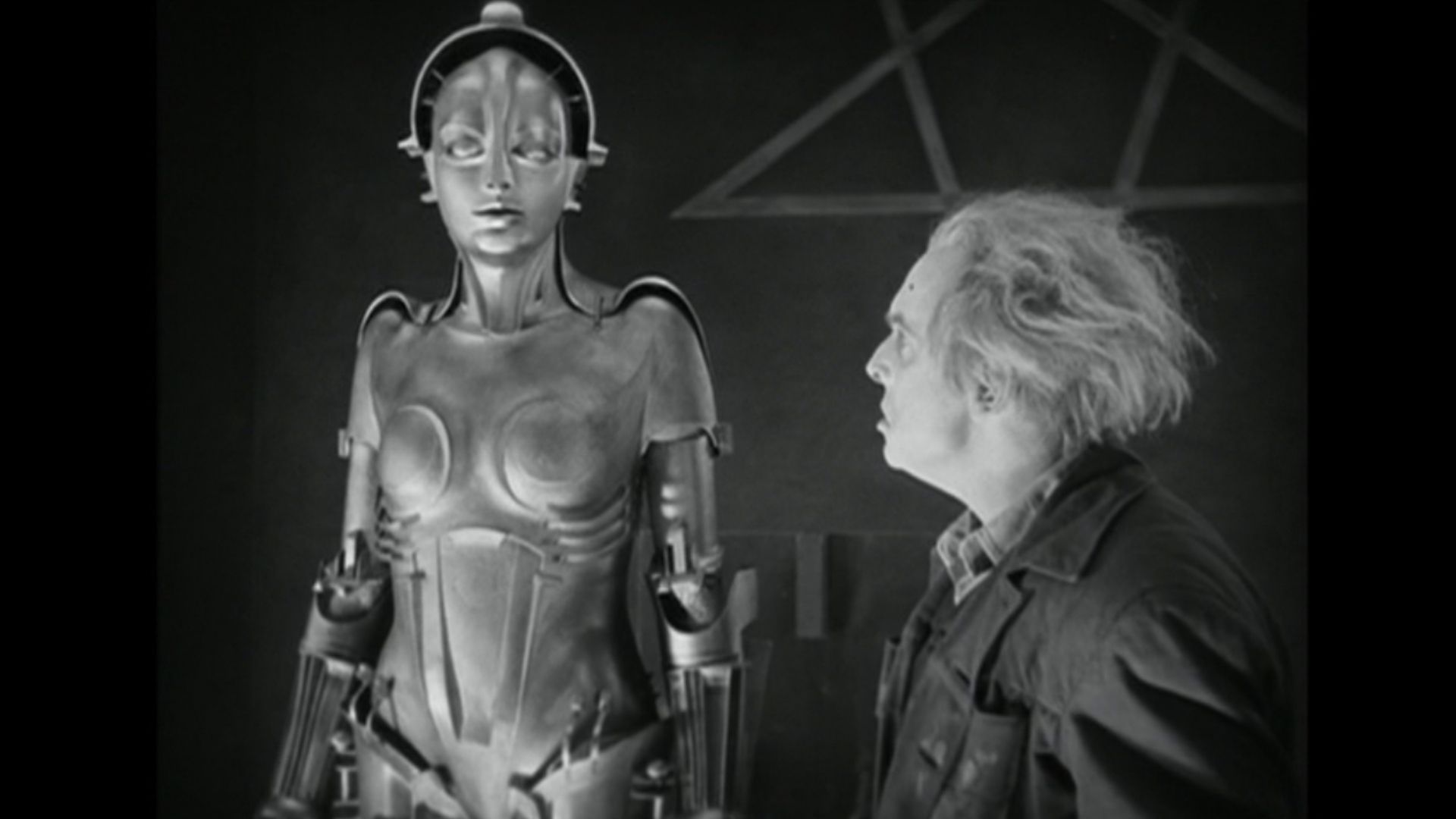

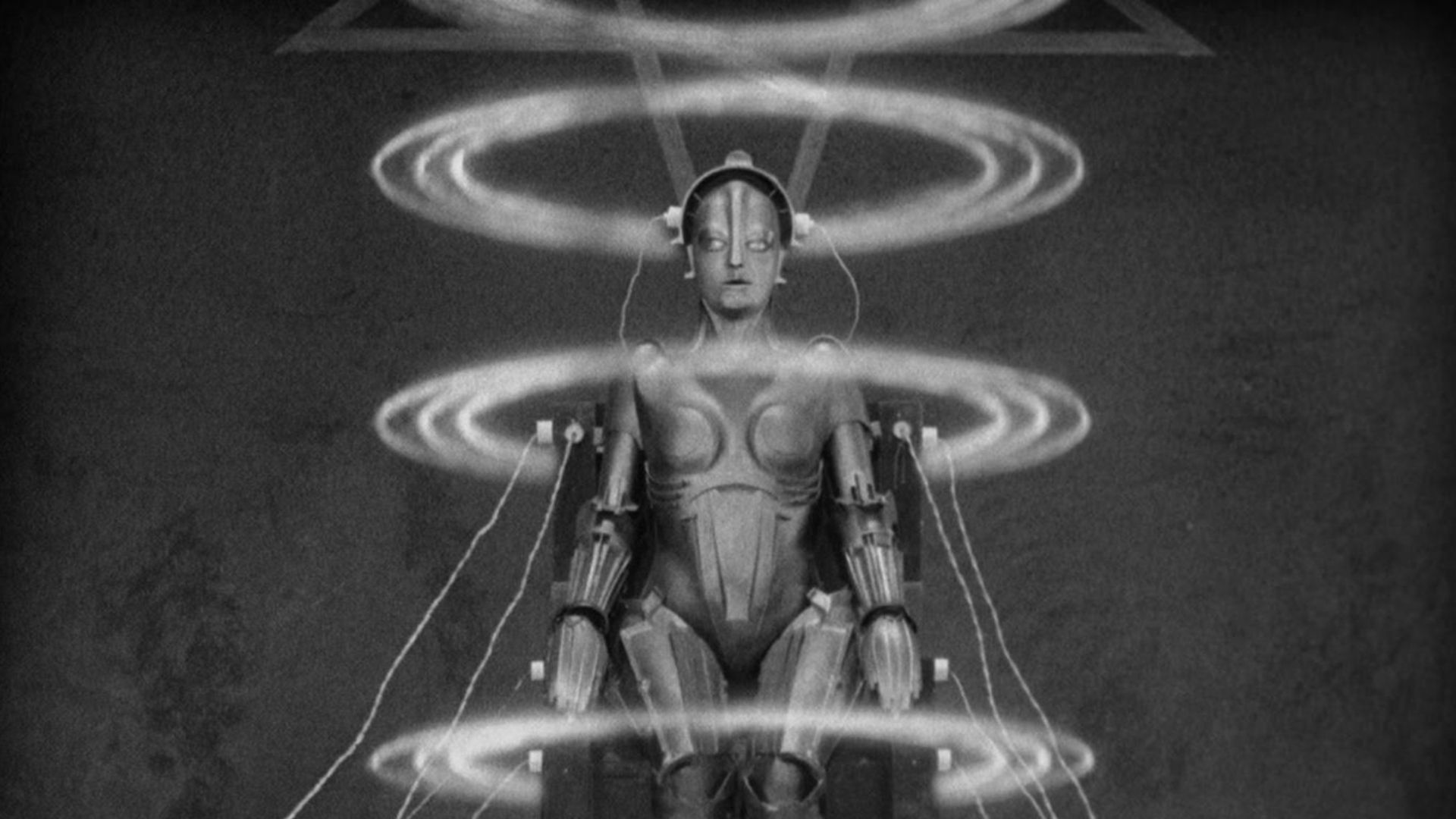

Among all the intellects that blossomed from Central Europe during the silent film era, it’s Fritz Lang whose influence is most profoundly felt. His masterfully constructed espionage thriller, “Spione” (or “Spies”), released in 1928, paved the way for the James Bond series. Always eager to venture into uncharted territories, he delved into sprawling crime epics such as “M,” featuring a future star Peter Lorre, and the gritty “Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler” (1922).

Contrary to its current acclaim among artists and critics, Metropolis (1927) served as a pivotal moment in the history of cinema, but not necessarily in a positive way. It’s more accurately described as a cult classic due to its initial financial failure. The producer, Erich Pommer, was ousted before its release for allowing extravagant budgets, which ultimately proved disastrous. Under new management, costs were reduced, and there was constant friction with the staff, leading to the departure of talents such as Billy Wilder and Marlene Dietrich.

The Party Comes to an End

The golden era of cinema came to an end with the rise of Nazi rule, as films that challenged authority or traditional values were deemed “degenerate art” and banned. Many prominent filmmakers and actors, some of whom had Jewish ancestry, were hostile towards Hitler, which didn’t help matters. Within a year, Fritz Lang, a key figure in German cinema, was divorced (his wife/co-writer was secretly a Nazi) and left the country, continuing his work in Los Angeles. It is said that the German propaganda minister and his superior were so impressed by Lang’s work in Germany’s film industry that they offered him the position of running the nationalized UFA studios, although this account has been disputed by historians. Hitler, interestingly enough, was a fan of Mickey Mouse cartoons, but Walt Disney was too occupied to take up the offer.

By 1934, the golden age of German cinema had come to an end, and those who took over were determined to undermine foreign films. They even went as far as to appoint a special representative in Los Angeles whose job was to sabotage studios that planned movies which tarnished Germany’s international image.

After Murnau, Lang, Lorre, and Veidt, along with many other notable stars, departed, only Emil Jannings and Pabst remained as significant figures still working in Germany during World War II. These two were among the very few globally renowned celebrities who continued to create films in this period. While remakes and sequels continued, often by the same creators as before, they failed to reach the same heights of success. The once-promising movie industry center eventually became a shadow of its former self with the advent of “talkies.” Unfortunately, German cinema has never regained its original glory since then.

On a positive note, film enthusiasts haven’t forgotten directors like Murnau, Lang, and Wiene, as demonstrated by Eggers’ recent revival. You can catch his modern take on Nosferatu in cinemas currently, but it might be best to leave the little ones at home for this one.

Read More

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- USD MXN PREDICTION

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Pi Network (PI) Price Prediction for 2025

- Gold Rate Forecast

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Brent Oil Forecast

- How to Watch 2025 NBA Draft Live Online Without Cable

- USD JPY PREDICTION

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

2024-12-25 23:02