As a film enthusiast with a heart for slow cinema, I must admit that the cinematic journey of “Youth” has left an indelible mark on me. Having had the privilege to traverse through its lengthy runtime, I found myself deeply entwined with the lives of Zhili’s textile workers.

Documentary filmmaking, by its very nature, can pose an impossible challenge at times. Similar to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, the act of filming a subject inherently alters their essence – people become aware of the camera, and editorial choices reveal subjectivity. This topic has been extensively discussed, and filmmakers have explored various methods to circumvent or accept this paradox. Chinese director Wang Bing employs an innovative strategy that transforms his documentary style: he adopts a unique perspective on time, enabling viewers to fully immerse in the worlds he captures. For instance, his cinematic masterpiece, “Youth,” a trilogy focusing on textile workers, required five years of filming and four years of editing spread over those years.

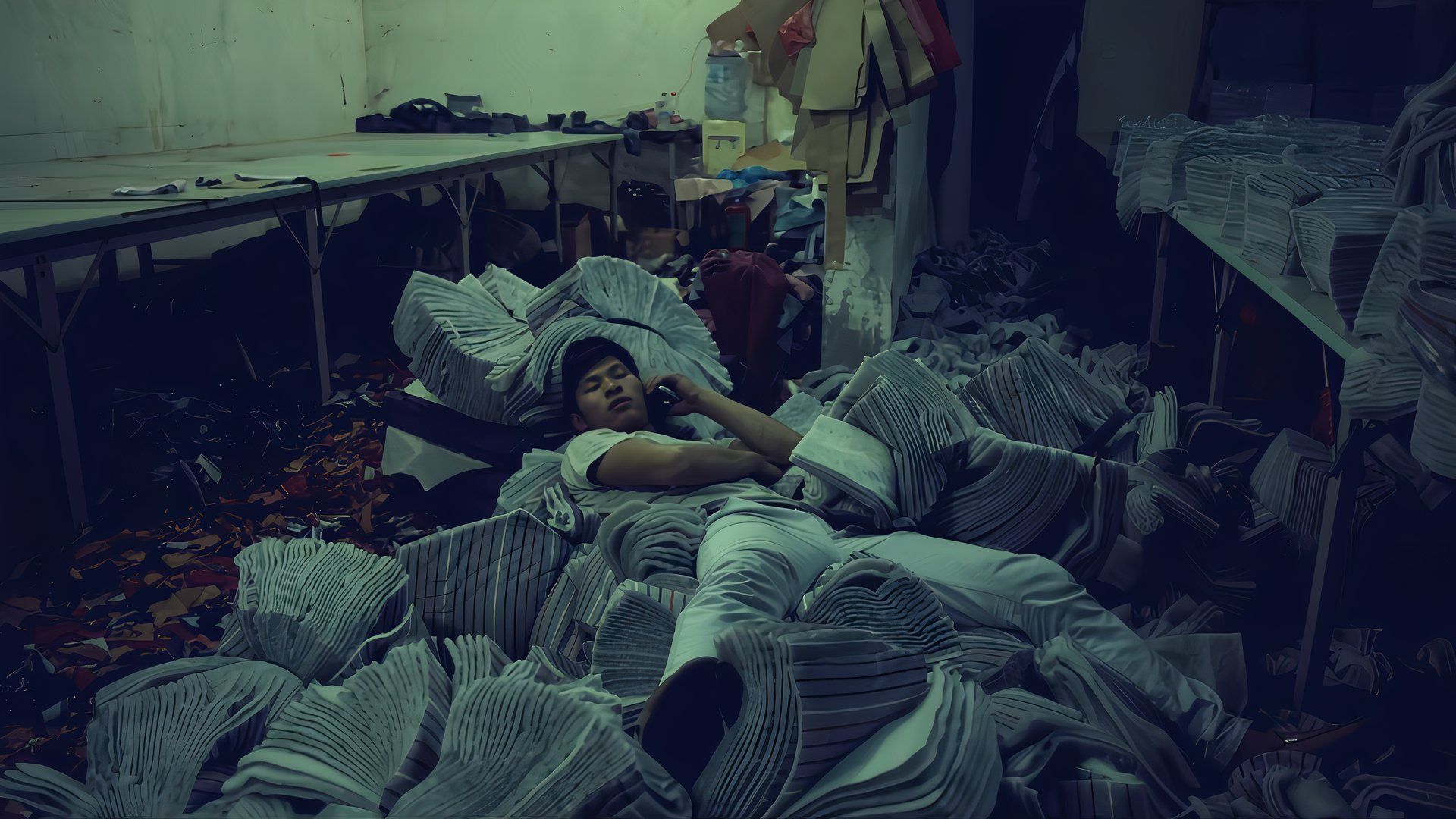

From 2014 to 2019, Bing immersed himself in Zhili, an industrial city approximately 150 kilometers from Shanghai, to delve into the lives of migrant workers who temporarily reside and work tirelessly for 12 hours or more each day. This initiative served as a precursor for the film titled Bitter Money, which Bing himself described as a trial run for this extensive undertaking. Additionally, he explored artistic expression through the installation called 15 Hours, featuring a 15-hour static shot of a single room where workers are seen working diligently.

Preparation was key for his “Youth” trilogy – a set of three interconnected yet distinct films that immerse viewers much like Bing did. Spanning approximately 10 hours across the three movies (specifically “Spring”, “Hard Times”, and “Homecoming”), “Youth” calls for profound patience and dedication, but it’s an enriching journey.

How Wang Bing Captured the Work of Youth

Approximately 300,000 individuals are employed in Zhili, with over 18,000 distinct companies operating. Bing examines numerous employees and various businesses, including their management teams; while each individual is unique, the overall picture takes on a haunting, melancholic quality that provides a comprehensive study of labor. The original plan allocated funds for six months of filming, but Bing extended it to a span of six years. There were six camera crews, rotating in shifts with three teams capturing footage simultaneously.

Bing explained the project’s essence and purpose to Projektor, stating, “The story is straightforward. I aimed to portray the reality of China post its significant economic reforms in the 1980s, focusing particularly on the Yangtze River Delta region. To be more precise, I wanted to highlight how individuals from rural areas upstream of the Yangtze River migrated to urban centers in search of employment. Most of these people were farmers who eventually transitioned into temporary workers.” Additionally, he mentioned:

I didn’t merely aim to understand their feelings; I wished to experience life from their perspective. I sought to stand alongside them, ensuring my perception mirrored theirs authentically. Rather than viewing them superior or inferior, I desired to regard them as equals, sharing the same level of reality.

Over the years, Wang Bing integrated himself seamlessly into the workers’ community, much like a fly on the wall would do. As he put it in an interview with Metrograph, “Our team resides in a nearby town; we arrive in the morning, film throughout the day, and depart at night. The process of understanding our subjects, learning about all the diverse characters and personalities in one particular location, and building trust to capture authentic moments takes a significant amount of time. It’s through this time-consuming process that we manage to acclimate ourselves to their environment.

Marrying Form & Content with a Decentralized Structure

Wang Bing paints a picture rather than constructs a story in his work titled Youth. Unlike traditional narratives with a clear sequence, the various ‘scenes’ don’t follow each other in a way that suggests a movie plot. Instead, we encounter numerous characters, most of whom are aged between 16 and 25, although some may be older. Our interaction with these individuals can last anywhere from 15 minutes to never seeing them again. The work provides no indication of the passing of time, whether it’s day or night, month or year. We only know which factory we are currently observing.

In this film, the disjointed narrative style echoes the transient nature of the characters. The workers, lost in the bureaucracy, merge into one mass, some returning for another stint, others not. They constantly enter and exit Zhili, performing the same monotonous tasks every day. Their living quarters are cramped and unhealthy, the days seeming to blur together. Each group attempts to bargain for better wages, only to be met with refusals or minimal increases by management. The phrase “time is money” rings true here as we witness the exchange unfold almost instantly. This fragmented style of “Youth” is ingenious; it reflects these people’s lives and the decentralized economic system in China, as explained by Wing Bang to Film Comment.

As a movie buff, I’d put it this way: “Back in China’s production facilities, there was once a strict, centralized system that ruled all aspects of work. Deviate from their methods, and face punishment. Now, it’s a different story. It’s all about the money, making it simpler to manipulate people with the lure and pressure of earnings. The more you produce, the more you earn.

The period of Youth (Spring) is characterized by its lack of structure. Unlike other documentaries, Bing doesn’t offer narration, interviews, dramatizations, or typical documentary elements. Instead, it presents a series of vignettes depicting the daily lives of people in various settings.

A Groundbreaking Achievement in Time & Proximity

In the realm of filmmaking, time serves as a potent instrument. Unlike the fast-paced cuts common in contemporary blockbusters, the allure of slow cinema lies in its hypnotic quality. However, this genre calls for an audience with a discerning palate, and regrettably, many have been conditioned to swift impatience. To be fair, Youth may leave most viewers feeling bored within mere minutes. Overcoming that initial urge to fidget and grappling with your own agitation is crucial before you can immerse yourself in the deeply human realm of Zhili.

Gradually, hour by hour, as you’re enveloped by the continuous hum of sewing machines, you find yourself merging with this environment. You develop a sense of kinship with the workers, understanding their daily rhythms. You share their hope and despair, cheering for specific individuals. At times, you grow tired of them, observing them seemingly lost in a phone screen, watching an amusing animated video without any noticeable change in mood. Bing’s camera gets incredibly close to these people, even invading their shared living and working spaces. The prolonged exposure and proximity contribute significantly to the immersive experience and fostering of empathy. As Bing explained to Film Comment, “…the deep runtime and deep proximity help with the immersion and ultimate empathy.

In crafting this trilogy, I aimed to revisit the essence of photography: a tool for capturing, chronicling, and documenting moments. To achieve this, I was passionate about maintaining an intimate proximity with my subjects, not just in terms of physical space but also in fostering an emotional bond. This intimacy encompasses our shared human experiences. I sought to immortalize the ordinary and everyday instances, believing that these are the moments worth preserving. The only way I can accomplish this is by spending extended periods with them, allowing me to truly observe, record, document, and chronicle their journeys.

It’s truly captivating to experience the sense of unity with individuals from all around the globe while seated in a cinema, thanks to films like “Youth.” This cinematic series fosters empathy and offers genuine insights into the lives of workers worldwide. We forge connections through our shared struggles, the monotony of our existence, the unfulfilled aspirations, the minor triumphs, and tender affections. The profound beauty in a grand epic like “Youth” lies in its ability to be enjoyed independently, but it’s the trilogy that carries us away on an extraordinary journey.

Read More

- USD MXN PREDICTION

- 10 Most Anticipated Anime of 2025

- Silver Rate Forecast

- Pi Network (PI) Price Prediction for 2025

- USD JPY PREDICTION

- How to Watch 2025 NBA Draft Live Online Without Cable

- USD CNY PREDICTION

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Gold Rate Forecast

- PUBG Mobile heads back to Riyadh for EWC 2025

2024-11-07 06:02